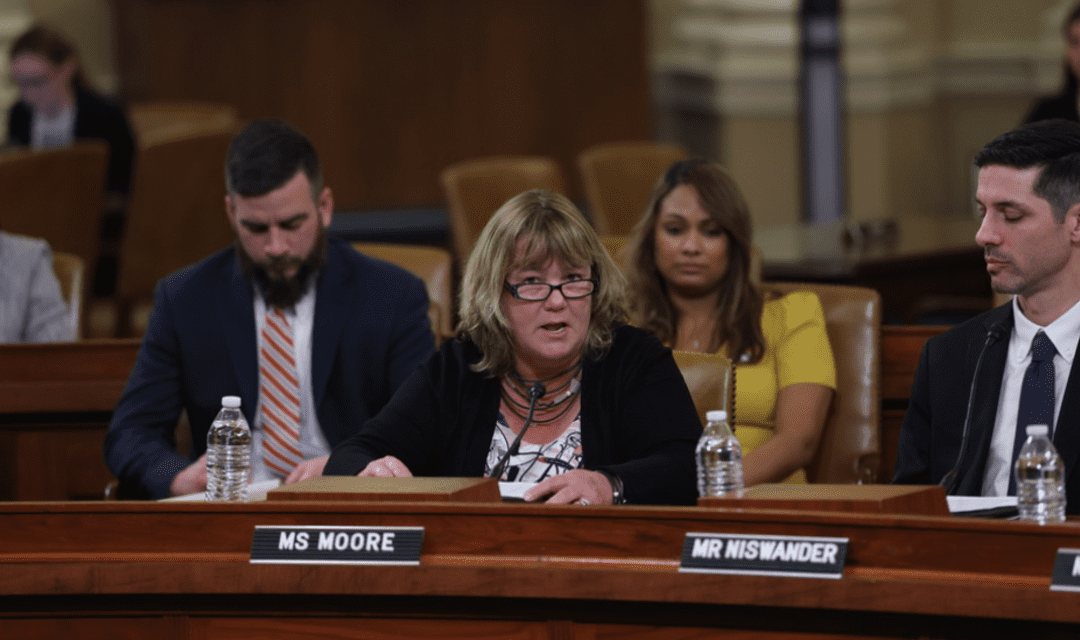

Last March, small-business owner Kelly Moore testified before the House Ways and Means Committee about what she considers the worst day of her life, when she had to announce to the employees of her GKM Auto Parts stores in Ohio that she would no longer be able to offer them health benefits.

“It was a gut-wrenching decision to make. I lost sleep,” she said.

The decision came in 2017 after years of trimming benefits — first she cut coverage for spouses, then dental and vision, life insurance, and she subsequently scaled back the employer contribution from 80% to 70% to 60%. A year later, thanks to a 20% tax savings from the Qualified Business Income (QBI) deduction going into effect and the ability to consolidate with other NAPA-affiliated companies as an association, the company was able to restore benefits.

But now, like many small-business owners, Moore is under attack again. Healthcare costs keep rising by up to 40% per year, and the QBI deduction will expire after 2025 unless there is further Congressional action.

“‘We have been in a crisis mode for nearly 40 years.’”

For small-business owners, this is the No. 1 business priority — and it has been for several decades that the National Federation of Small Businesses has been surveying its members. “We have been in a crisis mode for nearly 40 years,” says Josselin Castillo, manager of federal-government relations for the advocacy group.

Read: Small-business owners face a punishing cocktail of labor shortages, inflation and rising rates. But some are finding fresh ways to thrive.

The conundrum is this: Small-business owners want to provide health insurance for their employees, but they can’t afford it.

“To get qualified talent, regardless of the business, you have to have it to hire anyone. It’s table stakes. Employees demand it,” says Jean Smart, chief executive of Penelope, which provides retirement-plan solutions to small businesses. On the contrary, only about 20% of the companies she works with that are starting 401(k) plans are doing it because new hires requested it.

Smart currently employs 12 people, up from four when she launched last year. Already in the two years she’s been managing the health plan, costs have gone up 10%. She says she has to budget 30% more than an employee’s salary to cover the costs. “So if I’m paying somebody $100,000, I have to budget $130,000,” she says.

Smaller businesses have less buying power

Some 99.9% of companies in the U.S. qualify as small businesses, according to the Small Business Administration, and these 33 million-plus companies employ more than half of the private sector employees in this country. Yet owners do not have the same buying power as large companies when it comes to group insurance plans.

The cost differences can be staggering. The NFIB’s Castillo points to the fact that the latest healthcare-cost survey of large employers by Mercer shows a rise of 5.4%, while most of her small-business owners are seeing 25% increases on average.

One roofer in Oregon is facing a 44% rise in premiums, and this may be the last year he’s able to offer benefits to his employees.

“It all depends on the risk pool of the market you’re in,” says Castillo. “If you’re a large employer, the pool is your employees and if you see a lot of diabetes, you can implement wellness programs. But small businesses are beholden to the whole state, and it’s the luck of the draw.”

Castillo says that 98% of her members think they will have to stop offering health benefits in the next 5 to 10 years if nothing changes in the dynamic. The calculus becomes one of risking employee retention versus customer retention. Right now, small-business owners are raising prices or taking profit losses to offset the rising costs.

“They try hard not to pass on to employees,” says Castillo. “This is the tension we’re living with.”

‘Everything is a spreadsheet’

Some are banding together to form associations, like Moore did in Ohio with NAPA-associated shops. Others are downgrading to Health Reimbursement Arrangements, where employers provide part of the cost for employees to buy their own health coverage on the private market.

Some are networking to find out their options. Smart was able to call upon a network of women business owners like Luminary, Chief and WeSuite, to scour the marketplace for healthcare options.

“This is what women do. For me, everything is a spreadsheet,” Smart says. “They gave me these 12-page decks with massive charts.”

Smart narrowed it down to three major questions she wanted answered: How much will it cost me, how much will it cost my employees and what doctors can we see? Then she spent about 12 hours selecting a plan. “I picked the one who explained it in bullets, versus 20 pages of charts,” she says.

Once she made her decision, Smart still spends a great deal of her time managing the plan and thinking ahead. “I’ve already called the plan manager because my costs have doubled from year one to year two. So next year, I need to be more proactive and preplan. You want to set it and forget it, but you need to think about it all the time.”