“Transition finance” is shaping up to be one of the new year’s most important subjects for anyone professing to care about the climate crisis.

There’s a “whole world of transition finance being created as we speak,” said Mark Carney, the United Nations special envoy on climate action and finance, during a panel discussion at last month’s COP28 in Dubai.

The conversation has “matured from talking about investing in climate to investing in transition,” said Annika Brouwer, a sustainability specialist at Ninety One Ltd. At least half of the South African asset manager’s engagements in Dubai focused on transition finance for emerging markets, she said.

The term was part of the final agreement among 200 nations in which they agreed to move away from fossil fuels. However, there’s lots of wiggle room. In the nonbinding deal, countries are called upon only to contribute to a global transition.

In other words, fossil-fuel companies have few boundaries in deciding how and when they will take part, said Ehsan Khoman, the Dubai-based head of commodities, environmental social and governance and emerging markets research at MUFG Bank Ltd (EMEA).

It also gives leeway to investors, including those with so-called sustainable mandates. The phrase “transition finance” is loosely defined as investments mainly in industries and infrastructure that help drive efforts to achieve a net-zero economy. It’s distinct from green finance, which generally targets so-called climate solutions like wind farms or battery plants.

Still, Chuka Umunna, JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s head of EMEA ESG and green economy investment banking, said the change in tone is opening doors to strategies that floundered just a few years ago. Concerns about greenwashing allegations previously thwarted efforts to develop a transition bond label for debt capital markets, but there’s now “much more of an appetite for discussion around that,” he said.

Coalitions of banks, insurers and asset managers are in discussions to put some guardrails around what constitutes transition finance. But for now, there’s no consistent standard.

The Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero is proposing that the investment strategy include financing of traditional green activities, like renewable energy or electric vehicles, as well as polluting companies that plan to decarbonize and even high emitters like coal plants—as long as they’re on the way to being shut down.

What unites most proposals around transition finance is the belief that, instead of simply cutting ties with high-emitting companies, financial institutions should help polluters either phase out their activities or put them on a so-called emissions-light pathway.

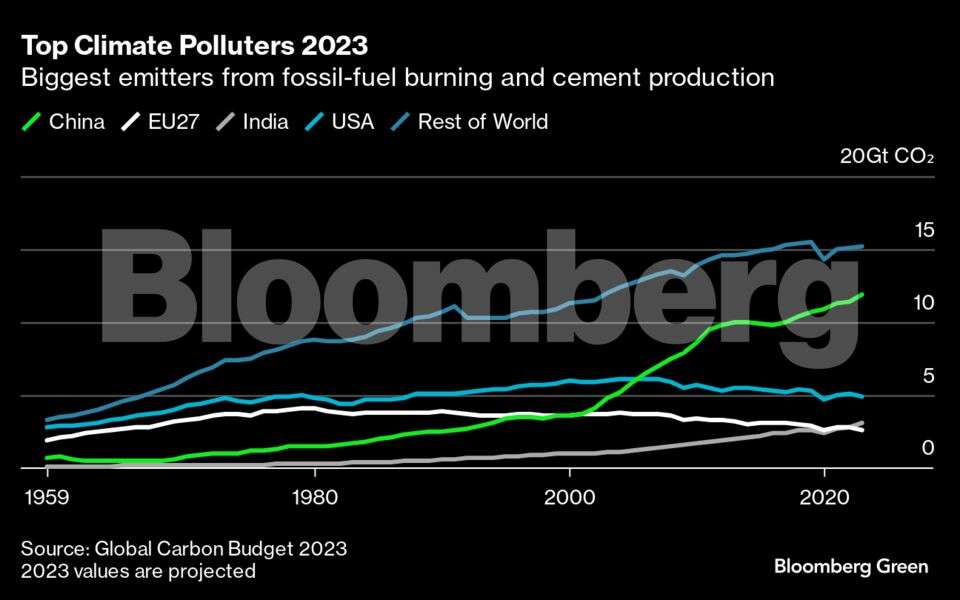

“You’ve got to go where the emissions are and try to bring those down,” said Curtis Ravenel, a senior adviser to GFANZ. The group is co-chaired by Carney, a former Bank of England governor who’s also chair of Bloomberg Inc., and Michael R. Bloomberg, founder and majority owner of Bloomberg News-parent Bloomberg LP.

For sustainability-minded investors, however, all of this begs the question: Do any assets fail to qualify? And for the polluters that do, how can investors be confident they’ll decarbonize at the speed and scale envisioned?

Such details are all the more critical given that some climate-finance funds announced at COP28 intend to invest in transition assets. For example, part of Alterra, a $30 billion venture that the United Arab Emirates launched with BlackRock Inc., TPG Inc. and Brookfield Asset Management Ltd., is going to transition funds. But there’s little immediate detail about how those are structured.

The way to “keep it honest” and avoid “the slippery slope” of investing in assets that aren’t in fact decarbonizing is to have established standards, said Nazmeera Moola, chief sustainability officer at Ninety One. Ideally, companies will be penalized if they fall short of their environmental commitments, she said.

“If you’re investing in a firm that’s claiming to transition, it’s got to have a really robust plan,” agreed Kate Levick, who leads E3G’s sustainable finance activities. “Regulatory expectations are firming up, but it’s a race to get there and also to converge so that we don’t get fragmented regulation gaps.”

Sustainable finance in brief

Norway’s largest pensions’ manager divested $15 million from Gulf companies on concern they may facilitate human rights violations, while also deciding to exclude Saudi Aramco because of climate risks. KLP, which oversees $70 billion, blacklisted a dozen companies listed in Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait from its investment universe. The divestments mostly reflect an “unacceptable” risk of contributing to human rights abuses, KLP said.

The excluded firms included companies in the real estate sector, where KLP says migrant workers from Africa and Asia have faced discrimination and human rights violations. “Gulf states remain characterized by authoritarian systems of government that restrict freedom of expression and political rights, including of critics and human rights activists,” said Kiran Aziz, KLP’s head of responsible investment, in a statement.