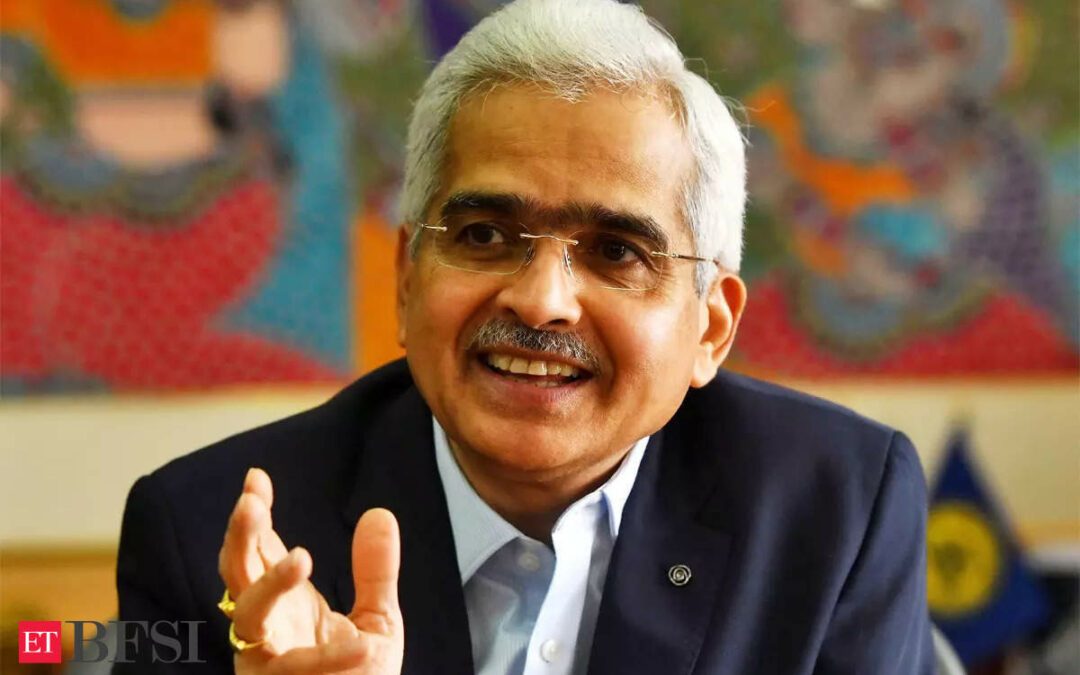

Reserve Bank of India Governor Shaktikanta Das’ message to the fintech universe is loud and clear: Just because a business is seemingly great doesn’t mean it has acquired the licence to flout rules. Amid noise from the startup ecosystem over the central bank’s decision to bar Paytm Payments Bank from business from February 29 for persistent violation of rules over seven years, the central bank said the only sacred thing in the financial world is the integrity of the system.

“All our actions, being a responsible supervisor, are in the best interests of systemic stability and protection of depositors or customers interest,” Das told reporters. “These aspects can’t be compromised. Individual entity should be mindful of these aspects for their long-term success.”

Das’s assertion comes after a bunch of entrepreneurs, including PB Fintech founder Ashish Dahiya, Bharat Matrimony’s M Janakiraman and others, wrote to the RBI and the government seeking a ‘review’ of the actions against Paytm Payments Bank.

They were ‘concerned about the potential ramifications of the current regulatory directive on Paytm Bank, extending far beyond the immediate impact on the company itself. This action, perceived as overly punitive, could send a negative signal to the global business community.’ But the governor has countered the projection of RBI’s action sending a negative signal to entrepreneurs. “The RBI is and will continue to support innovation and technology in the financial sector,” said Das.

Those lobbyists for Paytm may have to see that the regulatory action is not overnight. The regulator had done this after running out of patience due to repeated violations since its first year of operations. It was banned from onboarding customers in 2022.

On the contrary, the action or inaction of Paytm Payments Bank, which has stayed silent since the regulatory measures, puts a question mark on its governance and compliance standards. When its board is silent one of the stakeholders, One 97 Communications, is doing the talking.

The fintech ecosystem has to realise it has a well-established regulator – unlike the food delivery industry. The RBI’s actions are visible but not the process, giving a feeling everything is sudden. It is also rare that the regulator, which is mostly firm in its stand, goes back on its decision. At the peak of the liquidity crisis for NBFC, Indiabulls Housing Finance proposed to merge with the troubled Lakshmi Vilas Bank. But the RBI turned it down because of its belief based on the facts that the merger may not be in the best interests.

There were arguments that the proposal would save the RBI the painful act of bailing out LVB. But it stood its ground and arranged a marriage with DBS. When Yes Bank was teetering, distressed funds manager JC Flowers came to its rescue, but turning that down, RBI assembled a bunch of local banks to cut the cheque.

Financial regulators, especially the RBI, function in a way not so easily comprehensible for the layman. Their rules are the Bible. The priest in the church is kind enough to pardon the sinner the moment he confesses, but the regulators do so only after being convinced of reformed conduct.

“When the entity does not take any corrective action we go for imposing supervisory or business restrictions,” said Das. “Such restrictions that we impose are always proportionate to the gravity of the situation.” This is not changing at the RBI anytime soon.