Summary

- We share the market’s overwhelming expectation that the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) will leave the fed funds target rate unchanged at 5.25%-5.50% at the conclusion of its April 30-May 1 meeting.

- Stubborn inflation and resilient economic activity through the first few months of the year have left the FOMC little reason to ease policy in the near term. A chorus of Fed officials, which tellingly include a number of “doves,” has indicated that there is no hurry to cut rates at this time.

- An update to the Committee’s economic projections will not be released at the end of next week’s meeting, but the post-meeting statement and press conference will likely offer some clues on how the FOMC expects the policy path to evolve over the coming meetings.

- Since the FOMC’s March 20 meeting, we (along with markets) have pushed back our expectations for when the FOMC will start to ease policy. We currently expect the FOMC to first cut the fed funds target rate by 25 bps at its September 18 meeting, followed by another 25 bps point cut at its December 18 meeting.

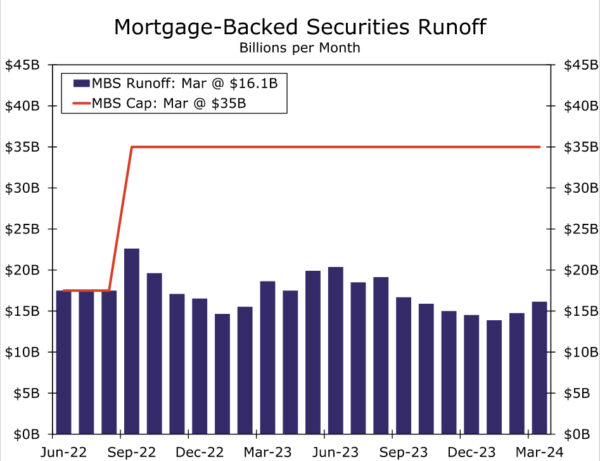

- We anticipate the FOMC to announce a change to its ongoing balance sheet runoff program at its upcoming meeting even as it leaves the fed funds rate unchanged. We expect the Committee to announce that, beginning in June, runoff of Treasury securities will be capped at $30 billion/month compared to the current runoff cap of $60 billion/month. The $35 billion monthly runoff cap for MBS, however, is likely to remain in place. The pace of MBS runoff, at $15-$20 billion per month, is already running well below the current cap.

- If we are off in our timing and the FOMC does not announce a slower pace of runoff on May 1, we would expect an announcement at the subsequent meeting on June 12. We anticipate this slower pace of QT running until year-end 2024. At its trough, we look for the central bank’s balance sheet to be roughly $6.9 trillion.

- We do not believe slowing the pace of QT will have a material impact on the level of interest rates. The outlook for the federal funds rate will be far more critical to determining the level and shape of the yield curve in the months ahead, in our view.

Recent Data to Keep FOMC on Hold

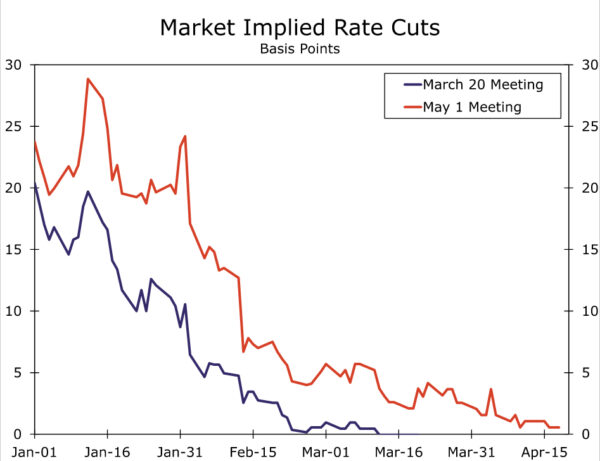

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) will hold its next policy meeting on April 30–May 1, and market participants overwhelmingly expect the Committee will maintain its target range for the federal funds rate at 5.25%-5.50%, an expectation we share. At the beginning of 2024, markets were essentially priced for a 25 bps rate cut at the March 20 meeting and a similar-sized reduction on May 1 (Figure 1). In the event, the Committee voted unanimously at its March meeting to keep rates on hold, and we look for another unanimous decision on May 1 to maintain the current target range. What has changed to induce the FOMC to keep policy unchanged so far this year rather than to ease as many investors had expected just a short while ago?

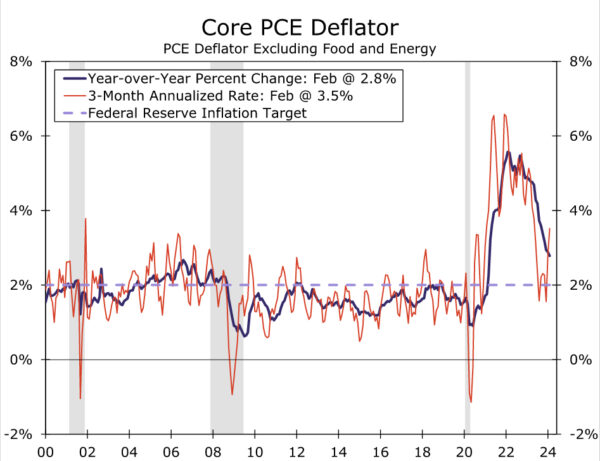

In short, inflation has been stickier and the economy more resilient than many observers had anticipated at the beginning of the year. The year-over-year change in the core PCE deflator, which Fed officials believe is the best measure of the underlying rate of consumer price inflation, slipped below 3% at the turn of the year while the deflator’s 3-month annualized rate of change moved to only 1.6% (Figure 2). Although the year-over-year rate has continued to edge lower, the 3-month annualized rate has risen, indicating that progress toward the FOMC’s target of 2% has stalled. Furthermore, data on real economic activity have generally been stronger than expected. For example, the economy created an average of 276K jobs per month in Q1-2024, up from 212K per month in the fourth quarter of last year. Stronger-than-expected data have led most forecasters to revise up their expectations for GDP growth this year. The consensus forecast for U.S. real GDP growth in 2024, as measured by the Blue Chip Panel of Economic Forecasters, was 1.6% in January. The Blue Chip forecast for this year now stands at 2.4%.

Fed Officials Indicate Little Urgency to Ease Policy

Sticky inflation and resilient economic activity give Fed policymakers little reason to ease policy in the foreseeable future. Fed Chair Jerome Powell noted on April 16 that “given the strength of the labor market and progress on inflation so far, it is appropriate to allow restrictive policy further time to work.” Recent comments by other Federal Reserve officials indicate that they too are in no hurry to cut rates. For example, Raphael Bostic, who is the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta and a voting member of the FOMC this year, recently stated “my outlook for 2024 is one cut toward the end of the year.” San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly, also a voting member of the Committee who many observers consider to be “dovish,” recently said “there’s absolutely, in my mind, no urgency to adjust the policy rate.” When a well-known dove is expressing skepticism about the need to ease policy, one should probably not expect a rate cut anytime soon.

As is customary for the April/May meeting, the FOMC will not release a Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) at the conclusion of this upcoming meeting. Therefore, market participants will need to rely on the post-meeting statement and Chair Powell’s comments during his press conference for clues about the FOMC’s outlook for monetary policy. The statement the FOMC released at the conclusion of its March 20 meeting noted that “economic activity has been expanding at a solid pace,” and that “job gains have remained strong, and the unemployment rate has remained low.” The statement went on to say that “inflation has eased over the past year but remains elevated.” Recent data indicating that economic activity generally remains resilient and that inflation has been sticky suggest to us that meaningful changes to that part of the post-meeting statement are not likely on May 1. We do not think the Committee will want to indicate that an easing of policy is imminent via a dovish statement.

As discussed in our recent U.S. Economic Outlook, we do not believe the FOMC will have the confidence it needs at its next two policy meetings (i.e., June 12 and July 31) about a return of inflation to the Committee’s 2% target to cut rates at those meetings. If, as we forecast however, payroll growth slows in coming months and the 3-month annualized rate of change in the core PCE deflator settles back down, then we look for the FOMC to cut rates by 25 bps at its September 18 meeting and by another 25 bps in the fourth quarter. But if inflation remains elevated and/or the economy remains resilient in coming months, then the timeline for the commencement of Fed easing likely would be pushed back even further, perhaps into 2025.

Quantitative Tightening Set to Begin Its Next Phase

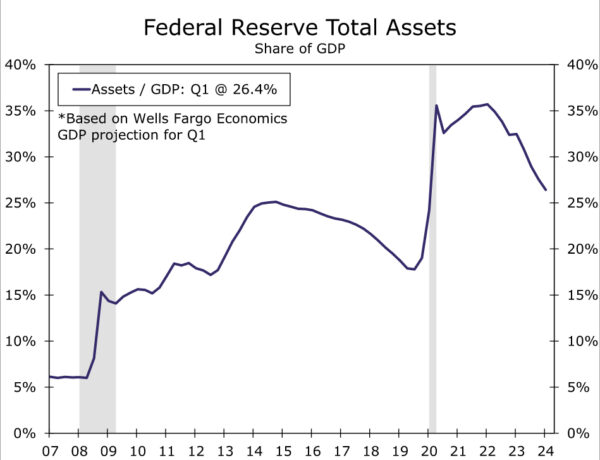

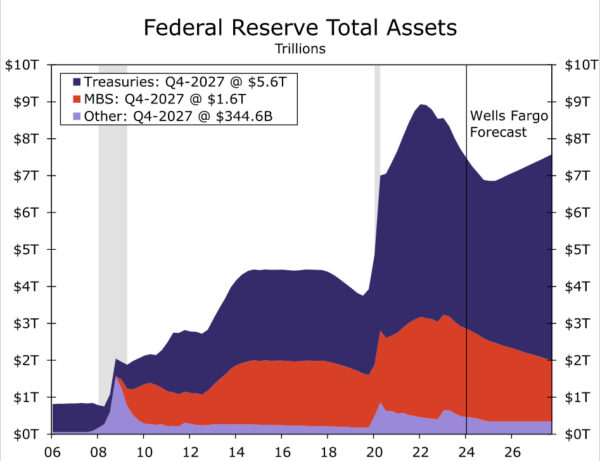

Although the FOMC likely will not change its target range for the federal funds rate at the upcoming meeting, we expect the Committee will announce some changes to its balance sheet runoff program, commonly referred to as quantitative tightening (QT). On June 1, 2022, the FOMC began allowing a maximum of $30 billion of Treasury securities and $17.5 billion of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) per month to roll off its balance sheet. In September 2022 these caps were increased to $60 billion and $35 billion, respectively, and they have subsequently remained unchanged. This passive runoff has driven a decline in the Fed’s balance sheet from a peak of nearly $9 trillion in Q2-2022 to $7.4 trillion today. As a share of GDP, the Fed’s balance sheet has shrunk materially, but it still remains larger than what prevailed on the eve of the pandemic (Figure 3).

Recent comments from Chair Powell and other Fed officials suggest the Committee expects to slow the pace of runoff “fairly soon,” a phrase we take to mean that a decision is coming at the May 1 meeting. The logic for slowing runoff is fairly straightforward: the ultimate “equilibrium” size of the Fed’s balance sheet is uncertain, and a prudent risk management policy calls for a slow-but-don’t-stop approach as the Fed feels out the optimal size for its balance sheet. The minutes from the last FOMC meeting noted that “slower runoff would give the Committee more time to assess market conditions as the balance sheet continues to shrink.”

We expect the FOMC will reduce the runoff caps for Treasury securities to $30 billion/month while it leaves MBS caps unchanged, with the new caps effective starting June 1. Note that MBS runoff has been running at roughly a $15-$20 billion per month pace, so the $35 billion cap has not been close to binding (Figure 4). If we are wrong and the FOMC does not announce a slower pace of runoff on May 1, we would expect an announcement at the subsequent meeting on June 12. We anticipate this slower pace of QT running until year-end 2024. At its trough, we look for the central bank’s balance sheet to be roughly $6.9 trillion (Figure 5).

Starting in 2025, we look for runoff to end and for the Fed to hold the size of its balance sheet flat for a couple of quarters. Such a move would allow the central bank to “grow into” its balance sheet, i.e., a flat balance sheet would still be shrinking as a share of the growing U.S. economy. At some point later in 2025, perhaps around mid-year or so, we expect balance sheet growth to resume to accommodate organic growth in Federal Reserve liabilities (e.g., paper currency and bank reserves). The Federal Reserve has continued to reiterate that it intends to hold primarily Treasury securities over the longer-run, and as a result we expect the FOMC will continue to passively reduce its MBS holdings in 2025 and beyond while replacing these MBS with Treasury securities, a move that would replicate what has occurred in the past.

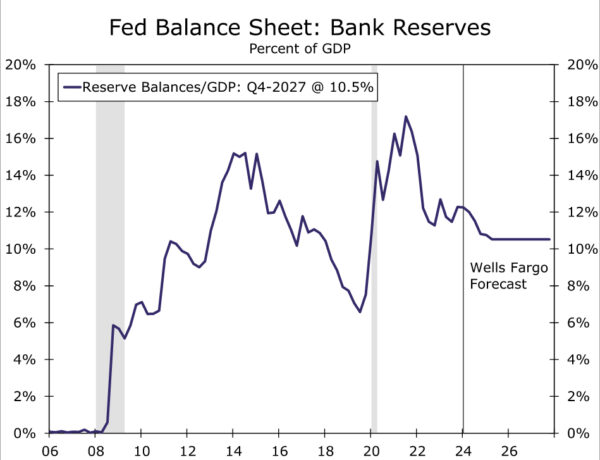

Where does this leave bank reserves? Bear in mind that bank reserves are the key swing factor in the Fed’s balance sheet. Commercial banks hold deposits at the Federal Reserve for a variety of regulatory and liquidity needs. The Federal Reserve aims to ensure that the amount of reserves in the system are “ample” but not overly abundant. Estimating the lowest comfortable level of reserves is a challenging endeavor and involves a mix of historical analysis, outreach to financial institutions and monitoring of money market conditions. Under our base case scenario, bank reserves decline in the coming quarters and eventually level off around 10.5% of GDP (Figure 6). If realized, bank reserves would be well below the pandemic peak but still comfortably above the amount that prevailed in September 2019 when a repo market blowup spooked financial markets.1 This analysis assumes paper currency in circulation continues to grow at trend, RRP balances are at low levels and the Treasury’s General Account holds steady at $750 billion for the foreseeable future.

We do not believe slowing the pace of QT will have a material impact on the level of interest rates. If the Fed’s balance sheet bottoms out a bit under $7 trillion as we expect, then runoff is already three quarters complete. Furthermore, the FOMC’s communication with the public on this topic is well established, and financial markets should be well-prepared for the pending change. The outlook for the federal funds rate will be far more critical to determining the level and shape of the yield curve in the months ahead, in our view.

Endnotes

1 – For further reading, see Anbil, Sriya, Alyssa Anderson, and Zeynep Senyuz (2020). “What Happened in Money Markets in September 2019?,” FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, February 27, 2020.