Summary

In recent times, the U.S. dollar’s status as the global reserve currency has been questioned, more so now that the reach of U.S. sanctions capabilities has been expanded to seize foreign government dollar assets. But despite the risk of having assets confiscated, in addition to recent efforts to diversify from the greenback, we continue to believe the U.S. dollar will remain the global reserve currency for the foreseeable future. Sanctions capabilities could also have a significant impact on China as official sector assets seem to have material exposure to the U.S. dollar and Western financial markets more broadly. U.S.-China geopolitical tensions, theoretically, should prompt China to make a concerted effort to move away from dollar and other advanced economy assets; however, China will face challenges in shifting away from the greenback.

U.S. Dollar Reserve Status Is Safe Despite Sanctions Reach

Over the past few years, the status of the U.S. dollar as the global reserve currency has come into question at times. Developments such as Brazil and China announcing clearing arrangements in each other’s currencies, energy exporting Middle East nations willing to accept renminbi as payment, as well as a possible BRICS nation common currency prompted suggestions that the dollar’s downfall was inevitable. In response to those suggestions, we published our perspective, highlighting that we do not believe the U.S. dollar would lose its reserve status at any point over the foreseeable future, and that we were not concerned about recent attempts to pivot away from the dollar. In the case of China and Brazil settling in each other’s currencies, the China-Brazil trade relationship is worth only ~0.40% of total global trade, far from material enough to result in noticeable de-dollarization. We also had doubts that Middle East energy exporters, most of whom operate under a fixed exchange rate regime to the U.S. dollar, would be willing to potentially put currency pegs at risk by generating less dollar revenues. And a BRICS common currency, in our view, is unlikely to gather momentum. BRICS countries have intra-bloc competing objectives—both geopolitical (China-India, Saudi Arabia-Iran) and economic (China-India, Brazil-South Africa)—that we believe would ultimately limit policymaking options for most nations in the bloc. Not to mention, we have been skeptical that BRICS nations would want to expose themselves to potential secondary sanctions from perceived or actual doing business with sanctioned Russian government and corporate entities.

While at the margin, the U.S. dollar could experience less use in trade or investment purposes as a result of these initiatives, we continue to believe there is no credible, reliable or viable alternative to the U.S. dollar. To that point, we see many characteristics that continue to indicate the U.S. dollar will remain the preeminent reserve currency going forward. To be considered a “reserve currency,” certain characteristics must be demonstrated. These attributes include being

- Freely convertible (i.e., not pegged and/or subject to capital controls)

- Widely accepted and used in trade and global transactions

- Backed by large and liquid debt markets easily accessible to foreign investors

- Not subject to political influence (i.e., associated with an independent central bank)

The U.S. dollar checks all of these boxes, and while other currencies are also associated with these characteristics, we believe issues exist that will prevent the dollar from losing its status. In Europe, the euro and British pound are freely convertible, not pegged, nor subject to capital controls; however, while sovereign debt markets are sizable, government debt markets are not as deep as the U.S. and are also somewhat segmented. Fragmentation is also a relevant regional risk and one that has gathered momentum since the euro was adopted. Brexit—as well as the risk of Frexit, Grexit, Italexit, Spexit and other percolating EU-fragmentation movements—in our view, is enough for FX reserve managers to at least pause when considering allocating an outsized amount to European currencies and respective Eurozone or U.K. sovereign bonds. For the Japanese yen, the government bond market has been, and continues to be, significantly distorted by the Bank of Japan (BoJ). The BoJ holds a significant majority of outstanding Japanese Government Bonds, and while Yield Curve Control has ended, yields on Japanese sovereign debt remain quite low. While the independence of the Bank of Japan is not in question, the BoJ’s substantial bond holdings are to some extent limiting accessibility to the JGB market by foreign investors, which also likely limits the yen’s ability to make headway toward becoming the dominant global reserve currency. Also, with the Japanese yen facing extreme depreciation pressures, Japan’s Ministry of Finance and BoJ policymakers have intervened more actively to support the yen. While the yen is not a managed currency, more government intervention in FX markets could make it less than ideal for FX allocators. And with respect to the Chinese renminbi and Chinese government bonds, capital controls and convertibility concerns as well as the managed exchange rate regime of the renminbi should provide disincentive for reserve managers to allocate currency holdings toward Chinese assets. Taking these factors into account, we see limited alternatives for FX reserve managers to U.S. government bonds and, accordingly, view the U.S. dollar’s status as the global reserve currency as secure for the foreseeable future.

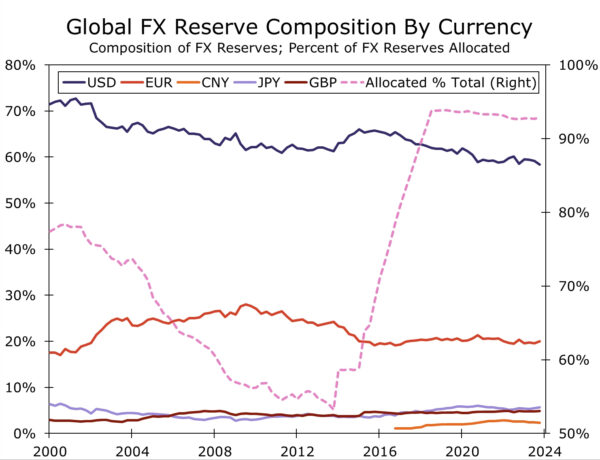

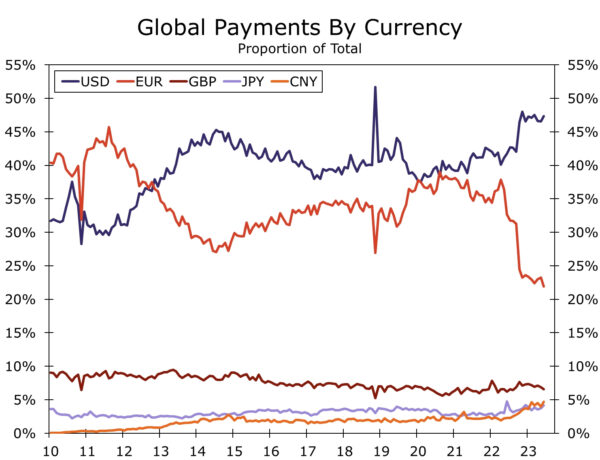

However, sanctions imposed on Russia following the invasion of Ukraine, as well as recently passed U.S. legislation, at least introduce a potential new vulnerability to the U.S. dollar’s world reserve currency status. For context, Russia’s FX reserves—more specifically dollar-denominated reserves held primarily in the U.S. and Western Europe—were frozen not long after the invasion of Ukraine as part of the overall sanctions regime. In total, ~$300 billion of Russia’s ~$600 billion FX reserves are currently unable to be accessed by the Central Bank of Russia, in effect frozen. Of this $300B, ~$5B is sitting within the U.S. financial system. For the past two years, U.S. policymakers have only provided authority to freeze the $5B of Russia’s FX reserves, not confiscate them. Meaning, as of now, all frozen FX reserves, whether located in the U.S., Western Europe or elsewhere, still belong to Russia. Fast-forward to last week, as part of the latest U.S. financial aid bill for Ukraine, Israel and Taiwan, President Biden has now been given authority to seize Russian assets held in U.S. banks, take ownership of $5B of Russia’s FX reserves, and direct those assets into a fund established to eventually rebuild Ukraine. While we will refrain from offering a view on whether this is prudent foreign policy, and whether President Biden will exercise his option to confiscate Russia’s assets, freezing and confiscating foreign FX reserves could present a problem for the U.S. dollar’s reserve currency status. The risk to the U.S. dollar’s reserve currency status stems from foreign central banks opting to reallocate their FX reserves away from the U.S. dollar to minimize confiscation risk should strategic views or geopolitical objectives not align with the United States. To date, central bank FX allocators have not been overly shaken by the possibility of assets being frozen or seized. As of the end of 2023, the U.S. dollar accounted for 58.5% of total central bank FX reserve assets, essentially unchanged from the 58.8% at the end of 2021 prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (Figure 1). In addition, and while a bit of a twist from central bank reserve allocations, since the onset of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, there are signs the use of the U.S. dollar in the global marketplace has increased. As of March 2024, and as measured by the SWIFT payments system, the dollar is used in over 47% of all payments, while use of the euro has fallen and other major currencies have not become integrated enough into payments systems to challenge the dollar (Figure 2).

China Is Very Exposed to a Russia-Style Sanctions Regime…

The possibility of central bank assets being frozen or confiscated puts China in an interesting position. Persistent U.S.-China economic and geopolitical tensions—which have broadened to include most Western and advanced economy governments—raise the possibility that a sanctions regime similar to that imposed on Russia could conceivably be imposed on China. Sanctions have already been placed on select Chinese corporate entities and individuals, but up to this point, the U.S. and U.S.-aligned nations have stopped short of sanctioning China’s central bank, sovereign wealth fund and state-owned banks. In a hypothetical scenario where the same Russia sanctions regime is placed on China, as best we can ascertain, a sizable portion of China’s FX reserves could be at risk of being frozen and/or seized. We say “as best we can ascertain” since China does not offer consistent visibility into the composition of FX reserves, and estimating the currency composition of China’s central bank assets is a challenge. On one hand, certain data sets suggest China is reducing its dollar assets. However, very compelling evidence suggests that, at a minimum, China has maintained a steady exposure to U.S. dollar-denominated assets, possibly even increased exposure to the dollar. These analyses suggest the decline in China’s U.S. asset holdings is due to the nature of financial and statistical reporting, in combination with techniques adopted by Chinese authorities. China could just be using alternative financial centers as the custodian location of central bank reserve assets. Other theories such as the PBoC shifting reserves to state-owned bank balance sheets or China having too many FX reserves and deploying excess assets toward China’s Belt & Road Initiative also exist and are possibilities we cannot dismiss.

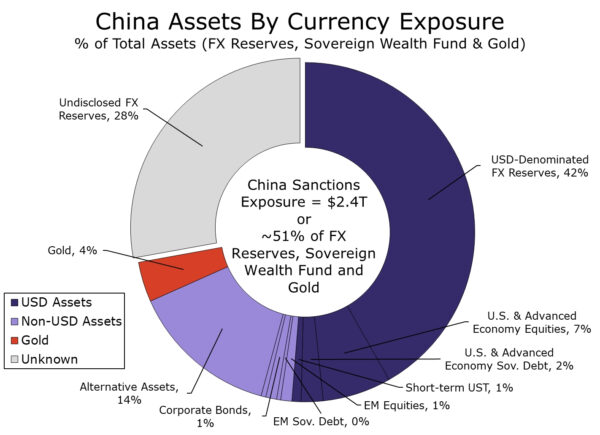

As intriguing as the evidence is around China’s potential use of financial techniques, we will use official published data to highlight and get a sense of China’s vulnerability to a coordinated sanctions program. As mentioned, the PBoC does not offer much insight into the composition of FX reserves, although it did disclose that ~60% of its reserve assets were held in U.S. dollars at the end of 2015. Given the lack of visibility and official data since then, we will assume 60% of China’s FX reserves are still held in dollar assets. The most recent People’s Bank of China (PBoC) data indicates that China has $3.25T of FX reserves. Applying that 60% ratio disclosed in 2015 leaves the PBoC with $1.95T of its FX reserves exposed to sanctions risk. We would also be remiss not to highlight the possibility that China’s sovereign wealth fund assets could also be at risk. Sanctions imposed on Russia also targeted Russia’s sovereign wealth fund, prohibiting transactions with Russia’s National Wealth Fund as well as freezing the fund’s assets held in the U.S. and Western financial systems. China Investment Corporation (CIC), China’s sovereign wealth fund, had assets worth $1.24T at the end of 2022. According to the CIC 2022 annual report, CIC allocated ~25% of total assets to U.S. and advanced economy equities, ~8% to advanced economy sovereign debt, and ~3% to “cash products,” which seem to be mostly short-term U.S. Treasury bills. In total, ~36% of CIC assets are held in U.S. and advanced economies financial assets—all of whom participated in the Russian sanctions regime and would likely coordinate again in a possible China sanctions program. The CIC’s asset allocation leaves ~$443B at risk of being frozen or seized. Combined with at risk central bank FX reserves, ~$2.4T of China’s total external buffer assets could be frozen or seized, or ~51% of China’s FX reserves, sovereign wealth fund and other assets such as gold (Figure 3).

…But, China Has Few, If Any, Options to Reduce Sanctions Vulnerabilities

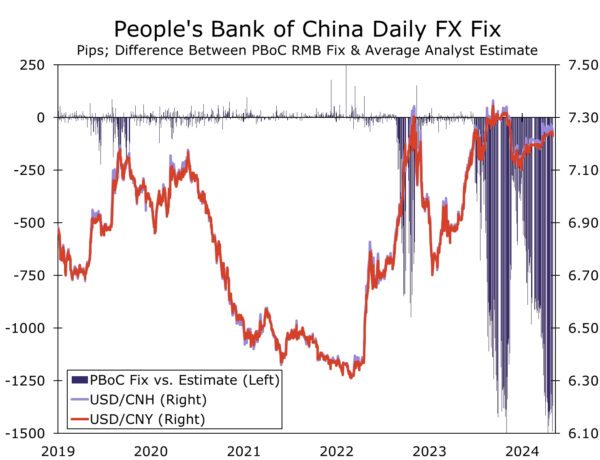

More than half of “official sector” assets at risk is a major vulnerability for China’s economy and financial markets. China’s large external asset buffers provide China with an exorbitant amount of financial influence, flexibility and freedom, and theoretically, should prompt Chinese authorities to consider allocating away from dollar-denominated assets and the currencies of Western financial markets more broadly. But China faces many challenges that complicates this shift. First off, the PBoC operates a heavily managed exchange rate regime. PBoC FX intervention to stabilize the renminbi or influence the currency in a certain direction is very common. While the PBoC may not target a specific level, policymakers do manage the USD/CNY and USD/CNH exchange rates. In order to intervene in FX markets as frequently as China’s central bank does and influence the USD/CNY and USD/CNH exchange rates, a large and available amount of dollar reserves is required. Sure, the PBoC could move to a free-floating, market-driven exchange rate regime to reduce sanctions risks and allow for diversification away from the dollar; however, at least at the current juncture, PBoC officials seem determined to achieve currency stability. For about a year, PBoC policymakers have set the overnight fix significantly stronger than analyst estimates in an effort to prevent renminbi depreciation (Figure 4). Even if PBoC policymakers did move to a market-driven exchange rate regime, that adjustment could also be costly. In August 2015, when the PBoC allowed for a one-time depreciation of the renminbi, China experienced large capital outflows that disrupted the local economy and caused a sharp selloff in local financial markets. In our view, China would prefer to protect against another round of capital outflows originating from currency depreciation. Aside from the overnight fix, PBoC policymakers tools to stabilize the renminbi include verbal intervention and interest rate hikes. Verbal intervention is more of a short-term policy tool, while raising interest rates is likely not a macro-prudential policy option given how fragile interest rate sensitive sectors such as real estate are, and how soft consumption is.

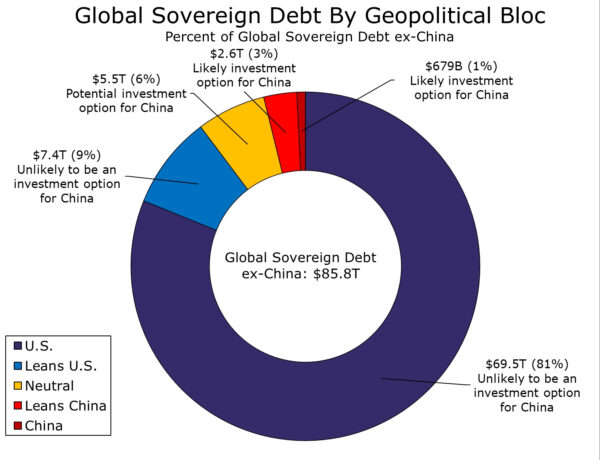

To illustrate an example, let’s assume PBoC policymakers did float the renminbi and reduce a degree of dollar dependency. China would likely still want and/or need to diversify away from its own currency and financial markets, and attempt to achieve some type of return on assets. The problem with China attempting to invest abroad comes back to the sanctions U.S. and advanced economy peers might now be willing to impose. Just about all the major economies, and certainly those that could be associated with a potential reserve currency option, participated in the coordinated sanctions on Russia. As of now, we have little reason to believe a similar coordinated sanctions program would not be placed on China if circumstances called for such action. Which raises the question, where can China safely invest its assets? To offer some guidance on this, we utilized our U.S.-China fragmentation framework, which is designed to identify countries that could align with the United States or form an allegiance to China should the global economy fracture as a result of intensifying geopolitical hostilities. Using our framework, we determine that 90% of the global sovereign debt market (ex-China) would likely align with the United States (Figure 5). We also make the assumption that in a fragmented world, these U.S.-aligned countries would also participate in a Russia-style coordinated sanctions program. Meaning, 90% of the sovereign debt market could be shut off to China as feasible or desirable investment options. Only 6% of the government debt market we identify as “neutral” and opting not to align with either the U.S. or China. These countries’ financial markets could be options for Chinese overseas investment. Caveats, however, related to neutral nations do exist, most notably that India flashes as opting for neutrality. India is important because the government debt market is large, though policymakers restrict foreign access to domestic bonds. While the percent of foreign investors allowed to participate in India’s sovereign debt market has risen over time, China would likely meet headwinds accessing India’s debt markets due to policy restrictions. Countries that would more fully align with China in a fragmented world would then represent the most feasible options. These countries represent a small sliver of the global stock of sovereign debt. While countries associated with strong creditworthiness are in this segment—such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates—opportunity to deploy a significant amount of China’s assets into these markets simply does not exist. For China to invest a material amount of its asset position into China-aligned nations, the PBoC and CIC would likely have to be willing to invest in less creditworthy nation financial markets and take on a significant amount of credit risk. Given half of China’s assets would already be frozen, we have our doubts deploying the remaining assets into credit risky markets would be considered prudent investing by Chinese investment allocators.

This is all a way of saying that the U.S. dollar, despite recent efforts to reallocate away from the greenback, is unlikely to lose its reserve status simply due to lack of alternatives. If one of the geopolitically tense relationships with the United States is likely to experience challenges moving away from the dollar, we doubt diversification away from the dollar will material momentum. Headline-grabbing news may continue to appear going forward, but in our view, these represent more noise than they do substance. Long live the U.S. dollar as the global reserve currency.