Summary

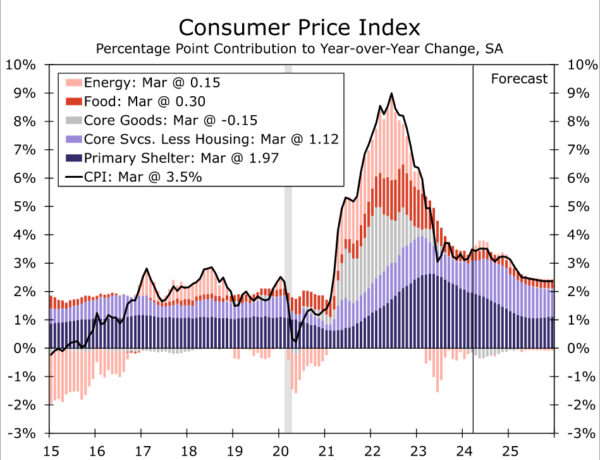

A string of uncomfortably-hot inflation readings in the first quarter leaves a narrow window for inflation to downshift before a late summer rate cut by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is no longer on the table. We expect the April CPI report to demonstrate that while inflation is not as sticky as the Q1 pace indicated, the journey back to 2% remains slow-going.

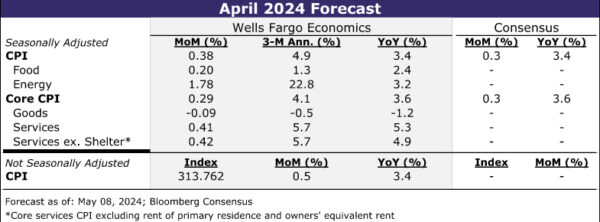

Headline CPI likely rose by 0.4% for a third consecutive month in April, which would leave overall prices running at nearly a 5% three-month annualized rate. Progress in lowering core inflation, however, likely resumed. Excluding food and energy, we estimate prices rose 0.3%, which would break the streak of 0.4% gains since January and push the year-over-year rate down to 3.6%, a three-year low. Ongoing deflation in the goods sector is expected to help keep a lid on core inflation in April, but services are likely to be the bigger driver of the softer print. We look for shelter inflation to have eased a bit further in April, and we anticipate a bigger step-down in core services ex-housing (+0.4% following a 0.6% rise in March).

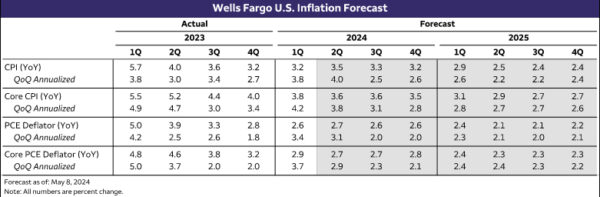

While inflation has been stubborn in recent months, we do not believe the underlying trend is re-accelerating. Supply chain pressures are not easing as rapidly as a year or two ago, but they are not building either. Shelter inflation looks set to moderate further this year, while services ex-housing inflation should benefit from tamer growth in goods-related input costs and gradual loosening in the labor market. We expect to see monthly inflation prints trend lower over the remainder of the year as a result, with the core CPI subsiding to a 2.8% annualized rate in Q4 and the core PCE easing to a 2.1% annualized rate in Q4.

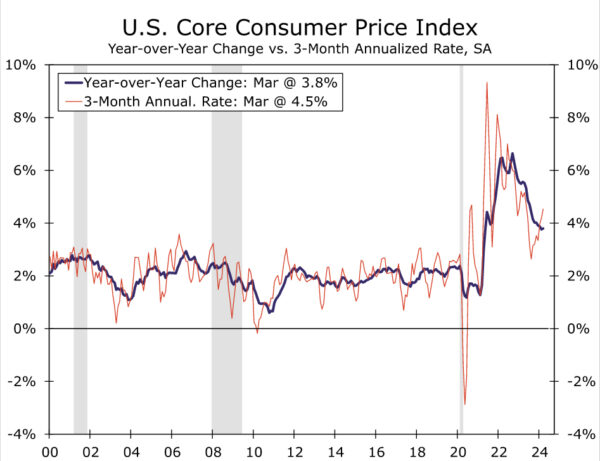

Downshift Needs to Resume to Keep a September Cut on the Table

Beginning with the April Consumer Price Index, Q2 inflation data will be crucial in determining whether early-year pricing strength was a brief detour on the road to quieting inflation or if the journey has gotten significantly longer. The FOMC made clear back in January that it would need to see additional benign data to be confident that price growth is on track to return to 2% on a sustained basis before reducing the fed funds target range. However, with core CPI and core PCE in March picking up to three-month annualized rates of 4.5% and 4.4%, respectively, the sufficient confidence has yet to be built (Figure 1). We suspect the FOMC will need to see at least three benign core inflation prints, perhaps even four, before easing policy, absent a rapid deterioration in labor market conditions. Thus, time is running out on the clock for even a late summer rate cut, and it creates the need for core inflation to downshift as soon as the upcoming April CPI report.

We expect to see progress in lowering inflation with the April CPI data, although improvement will likely be slight. Headline CPI looks set for another 0.4% increase, although that should be sufficient for the year-over-year rate to edge down to 3.4%—a tick lower than last month but still above the 3.1% rate registered at the start of the year.

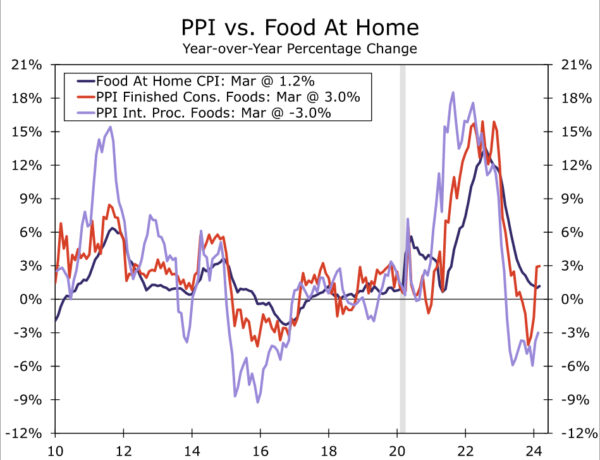

Similar to February and March, April’s headline strength will be partly attributable to another jump in gasoline prices. We estimate that once adjusting for the usual rise in prices at the pump this time of year, energy goods rose 3.0% in April. Falling oil prices in recent weeks, however, are teeing up at least a partial reversal in this component in May. Food prices, meanwhile, were likely a little firmer in April. An upturn in producer prices for consumer foods suggests grocery disinflation may be close to running its course, while two months of sub-trend gains in food away from home leaves scope for some mean-reversion in April. We look for food prices to rise 0.2% after a 0.1% gain in March (Figure 2).

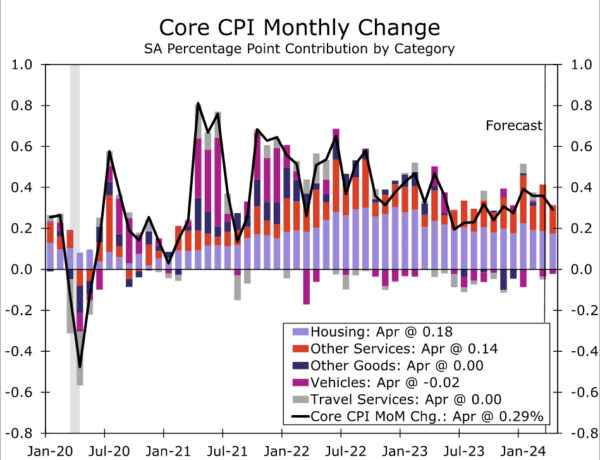

While headline inflation is likely to have remained firm in April, core inflation looks set to resume its downward trek. After three straight 0.4% monthly gains, we estimate core CPI rose 0.3% in April (Figure 3). If realized, the year-over-year rate for prices less food and energy would fall to a three-year low of 3.6%. Some additional deflation in the goods sector is expected to help core CPI slow in April. Both new and used vehicle prices look to have declined again, albeit at a more modest pace than in March. Elsewhere, goods prices were likely little changed in April, although a flat monthly reading would leave prices for core goods ex-autos down 0.8% over the past year—about double the average annual decline from 2014-2019.

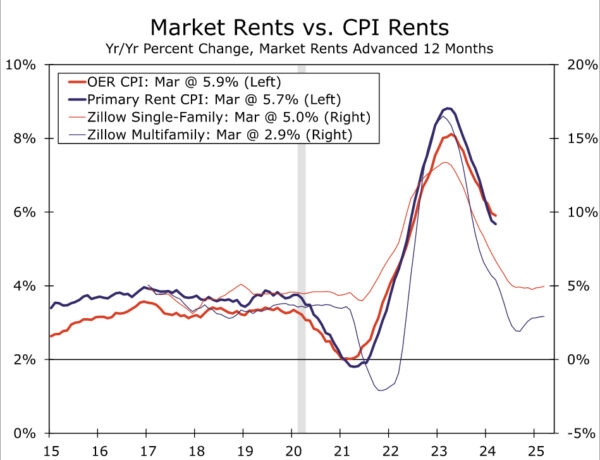

Services have been the more intractable component of inflation recently, making a downshift in this segment key to getting disinflation back on track. We estimate core services rose 0.4% in April, which would be the smallest monthly gain since December. Although the moderation in shelter inflation has unfolded slowly, the trend indicated by private rent measures as well as the CPI’s New Tenant Rent Index remains down; we have penciled in a 0.41% rise in primary shelter in April versus a monthly average of 0.46% in Q1 (Figure 4).

Outside of housing, core services inflation also looks to have eased a little in April. After rising 0.6% in March, we estimate the CPI equivalent of “super core” inflation rose 0.4% last month amid smaller monthly gains in medical care, motor vehicle, internet and personal services. If realized, the three-month annualized rate of CPI core services less housing would slow from 7.6% in March to 5.7% and suggest that the PCE “super core” advanced 0.3% month-over-month in April.

Outlook: Inflation Pressures Continue to Subside

The first quarter’s hotter price growth was indicative that further progress taming inflation will be slower ahead. Businesses remain more apt to raise prices than prior to the pandemic with sturdy consumer spending limiting the need to hold the line on prices. That said, we do not believe that the underlying trend in inflation is re-accelerating.

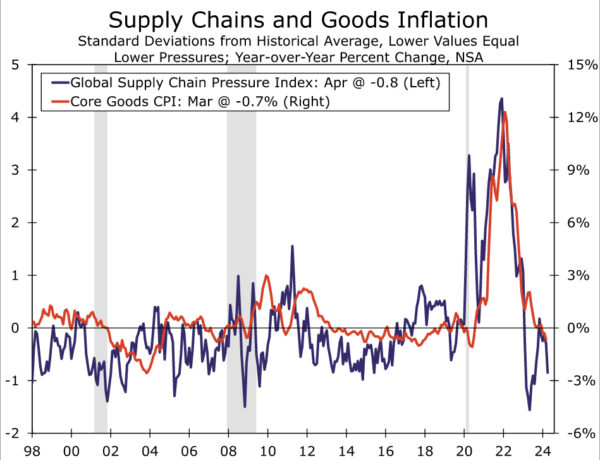

The strong disinflationary tailwinds to the goods sector over the past two years have faded, but upward pressure on goods prices remains minimal. Supply pressures are no longer easing as rapidly as in 2022 and the first half of 2023, but they are not building either (Figure 5). Margins in the goods sector also remain elevated relative to the 2010s, providing space for firms to ease up on pricing as consumers grow more discerning in their purchases. These dynamics should keep core goods in mild deflation territory in the near term. Similarly, food and energy-related commodities are not falling as sharply as over the course of mid-2022/early-2023, but range-bound levels over the past year or so mean food and energy’s contribution to headline inflation is not increasing materially.

With goods inflation likely to be little changed ahead, services will need to slow further to keep overall inflation on its downward trajectory. We believe the pieces are in place for services to contribute more to disinflation (Figure 6). Shelter inflation should continue to cool as we move through the year, with apartment vacancy rates climbing and deceleration in more forward-looking spot rents. We estimate primary shelter, currently up 5.9% year-over-year, will slow to 4.1% by December before bottoming out at a little over 3% around the middle of next year.

Outside of housing, upward pressure on services inflation also continues to ease. The steadier state of goods prices should usher in some relief to services inflation via tamer input costs, with motor vehicle insurance inflation likely being the most notable beneficiary of this dynamic. Meantime, the gradual loosening in the labor market is leading to slower nominal wage growth at the same time the trend in productivity has firmed. Overall, we see the still-elevated rate of services inflation early this year as largely a function of services being slower to respond to changes in the broader price environment this cycle, rather than a sign inflation is getting stuck at current levels. We look for core services to slow to 4.9% on a year-ago basis in Q4, which would help drive core inflation down to 3.5%.

Yet even as upward pressure on prices continues to subside, the first quarter flare up in consumer prices signals that inflation will likely take longer to fully stomp out than what the trend in the second half of last year implied. Progress on the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge looks set to be particularly slow. Amid the greater near-term momentum indicated by Q1 data and low base readings from late last year, core PCE inflation when measured on a year-ago basis is likely to be stuck around 2.7%-2.8% through the end of the year (Figure 7). Yet we continue to expect to see price growth slow on a monthly basis, with the three-month annualized rate on core PCE inflation falling back below 2.5% this summer. With the labor market continuing to soften, we think such a pace could still be enough for the FOMC to ease at its September meeting, but a string of more benign prints will need to start with the April data.