Wealth in Asia-Pacific has grown rapidly, but debt has spiraled upwards as well, while a few major markets saw their wealth contract, bucking the global trend, highlighted a latest report by UBS.

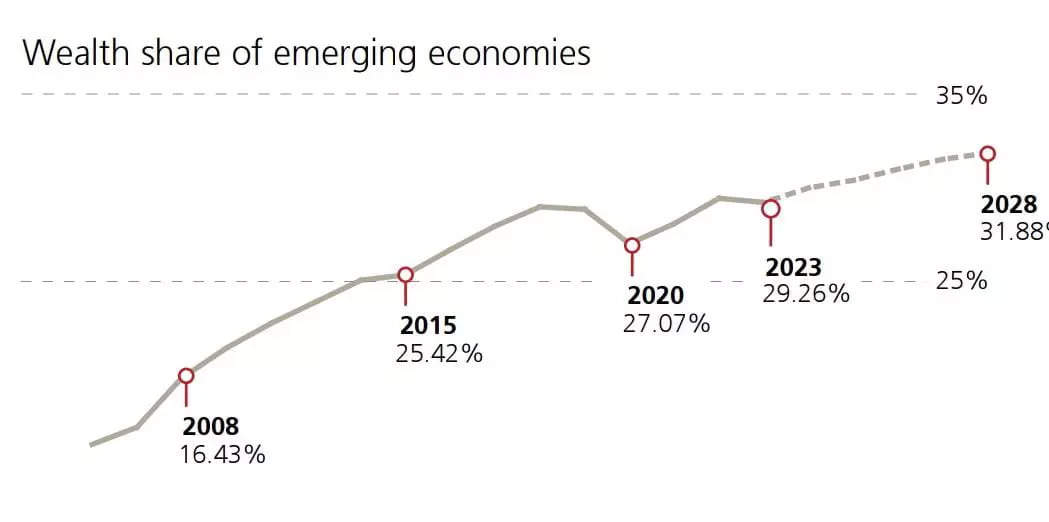

Over the past 15 years, it is Asia-Pacific that takes the lion’s share of growth in wealth, rising by nearly 177 per cent, followed by the America at nearly 146 per cent and leaving EMEA lagging far behind at just under 44 per cent.

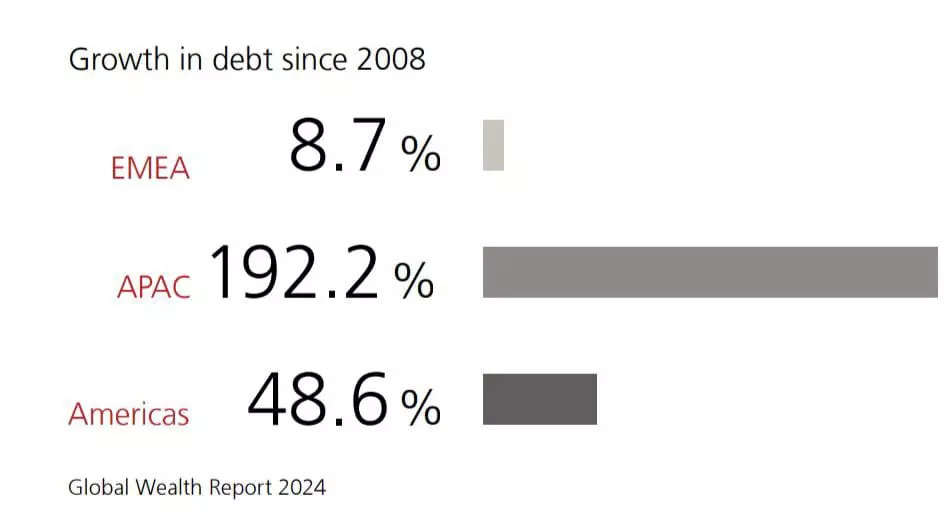

However, the Asia-Pacific region’s exceptional growth trajectory in both financial and non-financial wealth has gone along with a substantial spike in debt— total debt in this region has grown by over 192 per cent since 2008, more than twenty times the growth in EMEA and almost four times the figure for the America’s, said the report.

Debt growth in EMEA has been rather muted at under 9 per cent, far behind America at nearly 49 per cent. One reason for the comparatively low uptake in debt in the West may well be that many households in the US and in Europe had to pay back debt over the last decade following the Great Financial Crisis.

ALSO READ: US hosts most millionaires, strong rise in wealth brackets: UBS Report

Rising debt does not need to be a bad thing, per se. It is not uncommon for emerging economies to experience fast growth in credit as the financial system develops and matures, the report further elaborated.

It is rising prosperity that allows households to take on more debt, which up to a certain extent is entirely sensible, especially if it goes towards financing reasonably secure assets such as owner-occupied property.

It is only when bubbles develop in asset prices, investments are directed towards low-returning assets or the cost of servicing debt becomes crippling that alarm bells ought to ring. As emerging economies mature, their rise in debt should flatten out. If, instead, it keeps rising ahead of economic growth, it may be a reason of concern, said the report.

Wealth growth lost steam everywhere

While from one year to another the aggregate growth in wealth tends to fluctuate wildly, the long-term trend points to a gradual slowdown when measured in US dollars.

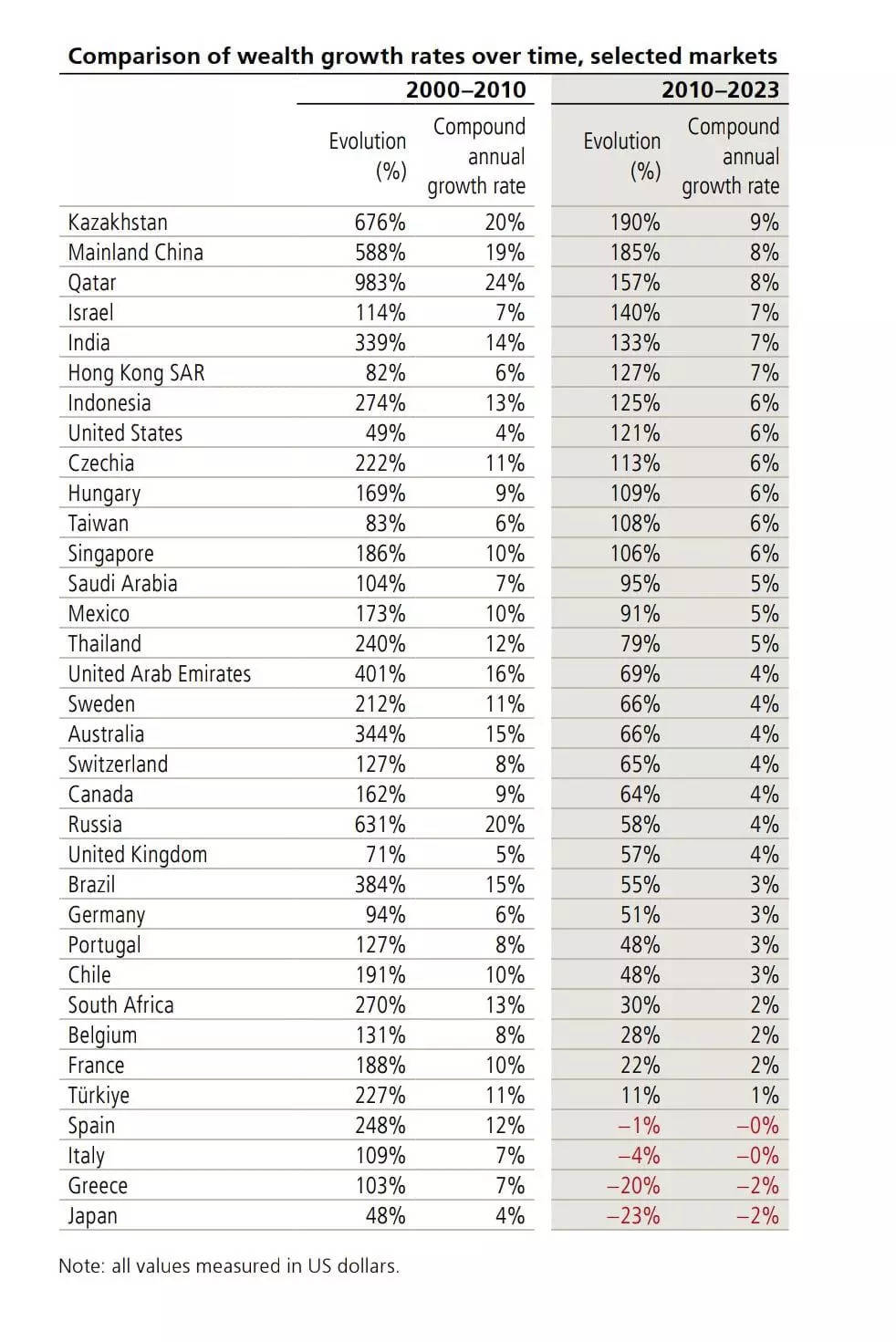

Overall, global wealth growth has cooled— it has fallen from an annual average of 7 per cent between 2000 and 2010 to barely over 4.5 per cent between 2010 and 2023. So about one-third has been chopped off, revealed the report.

In the first decade of the millennium, over half of the markets saw their wealth grow in the double digits when measured in USD. Since then, not a single one comes close to 10 per cent.

While there is a multitude of causes behind these developments, demographics no doubt play a role in the slowdown witnessed in Japan and Italy, since shrinking populations and ageing societies both tend to reduce the level of economic activity.

The strength of the US dollar with respect to most other currencies explains some of the slowdown. However, factors such as maturing economies in Asia-Pacific and Latin America as well as the sovereign

debt crisis in Europe also played a part, said the report.

This trend is nearly universal— it is shared by 53 out of the 56 markets analysed. The only significant exception is the United States, where average wealth growth has spiked from barely 3.7 per cent in 2000–2010 to nearly 6.3 per cent between 2010 and 2023.

This is in no small part due to the US being the epicenter of the Global Financial Crisis, with its negative impact on house prices, the main asset most people own. The slump in real estate depressed household wealth up to 2010, only to boost it in the following decade, low base of comparison that flattered the subsequent recovery.

The other two exceptions are Hong Kong SAR and Taiwan, but in both cases the increase in growth is far less pronounced, the report added.