Summary

- Congress has given the Federal Reserve a dual mandate of “maximum employment” and “price stability.” With inflation surging to a 40-year high in 2022, the FOMC largely has focused on its “price stability” mandate in recent years.

- However, inflation is showing signs of moving back toward the FOMC’s target of 2% on a sustained basis, and the labor market has softened somewhat recently. In short, the implicit weighting of the two objectives in the FOMC’s reaction function seem to be moving back into balance.

- We do not believe a consensus exists among FOMC members to cut rates at the upcoming meeting. But, we think the Committee will signal via its post-meeting statement that a rate cut could come as soon as its next meeting on September 18. Specifically, the FOMC likely will indicate it has seen more material improvement on inflation in recent months. We also expect the statement to acknowledge the Committee is now attentive to labor market risks as well, rather than focusing solely on inflation risks.

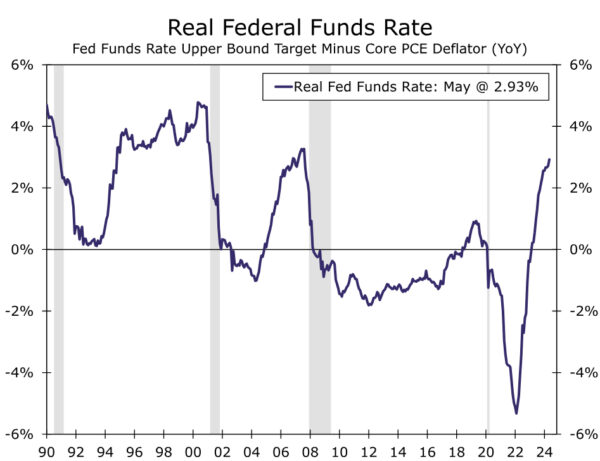

- The real fed funds rate has crept higher in recent months as inflation has receded. This passive tightening of monetary policy is another reason for the FOMC to consider policy easing in the not-too-distant future.

- In our view, the presidential election on November 5 will not preclude a rate cut on September 18, if conditions warrant. The historical record shows that political considerations do not seem to enter the FOMC’s calculus.

The Objectives of the Fed’s Dual Mandate Are Moving into Balance

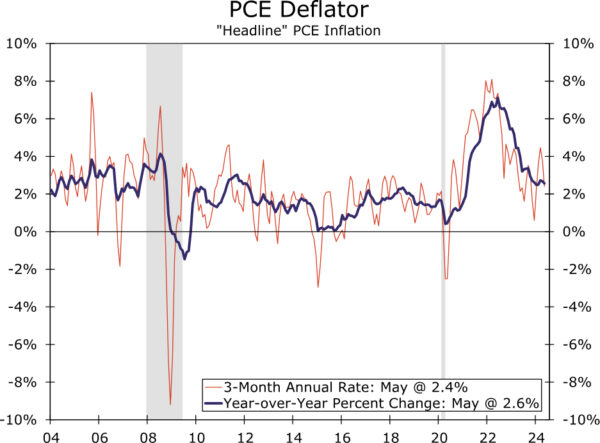

Congress has given the Federal Reserve a dual mandate: “maximum employment” and “stable prices.” The former is more of a theoretical concept than a precise target, but Fed officials have chosen to define the latter as a 2% annual change in the price index for personal consumption expenditures (PCE). Prior to the pandemic, when PCE inflation was consistently running at, or below, 2%, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) seemed to have placed equal weight on these two objectives when setting the stance of monetary policy. However, the surge in the year-over-year rate of PCE inflation to a 40-year high of roughly 7% in 2022 led the FOMC to focus almost entirely on the price stability part of its dual mandate (Figure 1). Consequently, the FOMC jacked up its target range for the federal funds rate by 525 bps between March 2022 and July 2023, the fastest pace of monetary tightening since the early 1980s.

However, the implicit weighting of the two objectives in the FOMC’s reaction function seem to be moving back into balance due to recent economic developments. For starters, inflationary momentum is slowing. The PCE price index rose at an annualized rate of 2.4% between February and May, down sharply from the 3.8% annualized rate that was registered in April (Figure 1). If our forecast of a 0.1% monthly increase in the PCE price index in June is accurate—the data are scheduled for release on July 26—then that three-month annualized rate of change will slow to only 1.3%. Inflation also appears to be back near the Fed’s target when looking at the less volatile core PCE index, which we estimate rose at a 2.0% annualized rate in the three months through June. Over the 12-month period ending in June, we expect both headline and core PCE inflation to have risen 2.5% and 2.6%, respectively. Although still above the FOMC’s 2% target, inflation has returned to a pace much more in line with recent history.

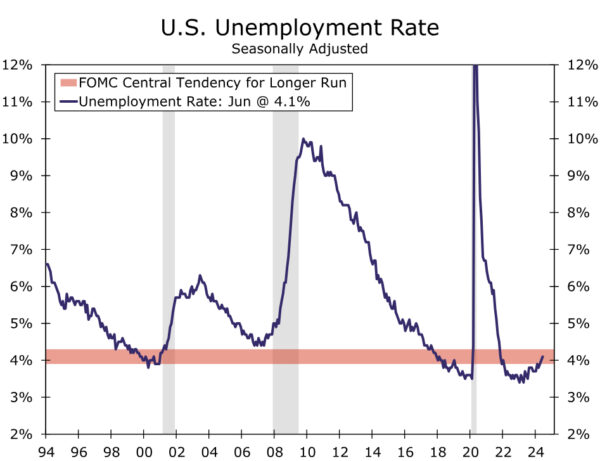

On the other side of the mandate, a number of indicators suggest that the labor market is softening. Growth in nonfarm payrolls slowed from an average monthly increase of 267K in the first quarter to 177K in the second quarter. The unemployment rate, which was as low as 3.4% in April 2023, has moved up to 4.1% (Figure 2). Continuing claims for unemployment insurance have risen to their highest level since November 2021, indicating it is taking longer for unemployed workers to find new jobs. The job openings rate, which measures total job openings as a percent of payrolls plus openings, has receded considerably over the past two years and currently stands near its level of late 2019.

Signal From Post-Meeting Statement: Rate Cuts Are Coming

With inflation having more clearly resumed its trek back to 2% and the jobs market no longer overheated, a reduction in the fed funds rate is coming closer into view. We expect the FOMC will hold its policy rate at its current range of 5.25%-5.50% at the conclusion of its upcoming meeting on July 31. But we expect the Committee will signal a rate cut could come as soon as its next meeting on September 18. While an updated Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) will not be released at this meeting, we expect the Committee will send a rate cut signal via changes to the post-meeting statement.

Specifically, the FOMC likely will indicate it has seen more material improvement on inflation in recent months than the “modest” further progress it noted in the statement from the June meeting. For example, it could say that there has been “additional” further progress, and this would be consistent with the Committee accumulating some “greater confidence” of inflation returning toward 2% on a sustained basis. In that regard, San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly, a voting member of the FOMC this year, recently stated “confidence is growing that we’re getting nearer a sustainable pace of getting inflation back down to 2%,” although she went on to note “we have a lot more information to get before we can make any real determination.”

We also expect to see the statement elevate downside risks to the labor market. The Committee may note that its employment and inflation goals are now balanced, rather than merely having “moved toward better balance.” The post-meeting statement has indicated for some time that “the Committee remains highly attentive to inflation risks.” We see a strong possibility the statement will add a clause indicating the Committee is attentive to labor market risks as well. That message was delivered by Chair Powell in his testimony to Congress earlier this month, and one that has been echoed by other FOMC participants over the inter-meeting period, including Governors Waller and Kugler, and regional Fed Presidents Daly and Barkin (Richmond–voter). In the same vein, a modest downgrade to the characterization of recent economic activity and labor conditions would not surprise us.

There has been a passive tightening of monetary policy in recent months, which is another reason to cut rates soon. That is, the stance of policy is measured by the real fed funds rate, not by nominal interest rates. We measure the real fed funds rate by subtracting the year-over-year change in the core PCE price index from the nominal fed funds rate (Figure 3). By that metric, the real fed funds rate currently stands near 3%, the highest level since 2007. Most observers, members of the FOMC included, believe the stance of monetary policy today is “restrictive.” Austan Goolsbee, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago and a voter at the July 31 FOMC meeting, suggested in recent comments that the need for policy easing is becoming more appropriate. Goolsbee noted that “we set this rate when inflation was over 4%, and inflation is now, let’s call it, 2.5%. This implies we have tightened a lot since we’ve been holding at this rate.” Holding the nominal fed funds rate steady while inflation has receded has led to a rise in the real fed funds rate; that is, there has been a passive tightening of monetary policy.

Although we believe it is highly likely the FOMC will remain on hold on July 31, the probability of a rate cut, albeit low, is not zero either. Some of the more “dovish” members of the Committee (e.g., voting members Governors Cook and Kugler, Presidents Daly and Goolsbee, and non-voting member President Harker (Philadelphia)) may argue during the meeting that the FOMC needs to “get ahead of the curve” by cutting rates in July or else risk a significant deterioration in labor market conditions in coming months. That said, we doubt a consensus exists on the Committee at this time to ease policy on July 31. The Committee could head off a potential dissent or two by some of these more dovish voting members by signaling in the post-meeting statement that policy easing is coming into view.

The “blackout period,” during which FOMC members refrain from making public comments, is now underway. So if policy easing at the upcoming FOMC meeting on July 31 really is under active consideration at this time, then policymakers would need to signal in coming days that a rate cut could happen at that meeting. Otherwise, market participants could be surprised, a development the FOMC generally wants to avoid because it believes policy is more effective when the public clearly understands the Fed’s intentions. Market participants could be given “heads up” that policy easing will be under active consideration on July 31 via a leak in coming days to a major media organization that is attributed to a “senior Fed official.” We doubt this is likely, but highlight it as a risk given that we believe an important inflection point in monetary policy is drawing near.

Will the November 5 Presidential Election Preclude a Rate Cut on September 18?

If, as we expect, the post-meeting statement on July 31 suggests that the time for policy easing is approaching, attention will naturally shift to the next policy meeting on September 18. Indeed, the rates market is essentially fully priced as of this writing for a 25 bps rate cut at that FOMC meeting. But will the FOMC change policy with the November 5 presidential election looming in the near future?

Chair Powell has repeatedly stressed that the FOMC will not allow political considerations to affect the Committee’s decisions regarding monetary policy. For example, Powell said on May 1 that FOMC members were “at peace” with keeping political considerations out of their deliberations. He went on to say “if you go down the road, where do you stop? And so we’re not on that road. We’re on the road where we’re serving all the American people, and making our decisions based on the data and how those data affect the outlook and the balance of risks.” Furthermore, the historical record supports Powell’s contention. The word-by-word transcripts of the FOMC meetings that have preceded previous presidential elections show that political consideration generally are not discussed. If, as we forecast, inflationary pressures continue to ease and the labor market softens further, then we believe the FOMC will reduce its target range for the federal funds rate by 25 bps at the September 18 meeting and by another 25 bps on December 18. For further reading on the historical record for FOMC policy decisions in election years, see the special report we published earlier this year, which can be found here.