By John Hawkins, University of Canberra

The 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics has been awarded to three US-based economists who examined the advantages of democracy and the rule of law, and why they are strong in some countries and not others.

Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James A. Robinson.

Nobel Prize Outreach

Daron Acemoglu is a Turkish-American economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Simon Johnson is a British economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and James Robinson is a British-American economist at the University of Chicago.

The citation awards the prize “for studies of how institutions are formed and affect prosperity”, making it an award for research into politics and sociology as much as economics.

At a time when democracy appears to be losing support, the Nobel committee has rewarded work that demonstrates that, on average, democratic countries governed by the rule of law have wealthier citizens.

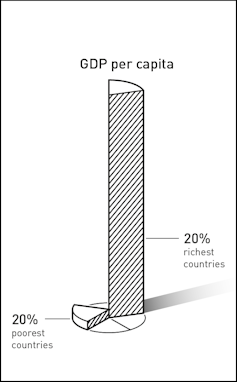

The committee says the richest 20% of the world’s countries are now around 30 times richer than the poorest 20%. Moreover, the income gap is persistent; although the poorest countries have become richer, they are not catching up with the most prosperous.

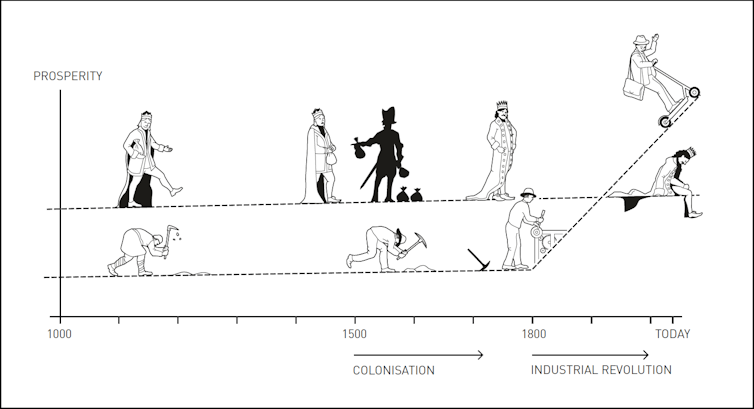

Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson have connected this difference to differences in institutions, and they find this derives from differences in the behaviour of European colonisers in different parts of the world centuries ago.

The denser the indigenous population, the greater the resistance that could be expected and the fewer European settlers moved there. On the other hand, the large indigenous population – once defeated – ofered lucrative opportunities for cheap labour.

This meant the institutions focused on benefiting a small elite at the expense of the wider population. There were no elections and limited political rights.

In the places that were more sparsely populated and offered less resistance, more colonisers settled and established inclusive institutions that incentivised hard work and led to demands for political rights.

The committee says, paradoxically, this means the parts of the colonised world that were the most prosperous around 500 years ago are now relatively poor. Prosperity was greater in Mexico under the Aztecs than it was at the same time in the part of North America that is now called Canada and the United States.

More so than in previous years, this year’s winners have written for the public as well as the profession. Acemoglu and Robinson are probably best known for their 2013 best-seller Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty.(It has pictures and no equations.)

Last year Acemoglu and Johnson published Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity.

In May this year Acemoglu wrote about artificial intelligence, putting forward the controversial position that its effects on productivity would be “nontrivial but modest”, which is another way of saying “tiny”. Its effect on wellbeing might be even smaller and it was unlikely to reduce inequality.

This year’s award makes the cohort of Nobel winners a little less US-dominated.

Although all three are currently working at American universities, Acemoglu is from Turkey and the others are British. There is even an Australian link. Robinson taught economics at The University of Melbourne between 1992 and 1995.

Winning the prize is life-changing for more reasons than the 11 million Swedish kroner (about $A 1.5 million) the winners share. As Nobel winners, they will have a higher profile. Their opinions will be accorded more respect by most but not all.

Sixteen former winners recently issued a widely reported statement saying they were “deeply concerned about the risks of a second Trump administration for the US economy”. Rather than address their arguments, the Trump campaign called them “worthless out-of-touch Nobel prize winners”.

The new winners might get the same treatment. Johnson has critiqued Trump’s proposal to raise tariffs. Acemoglu has called Trump “a threat to democracy”.![]()

About the Author:

John Hawkins, Senior Lecturer, Canberra School of Politics, Economics and Society, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.