At the spring meetings of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank earlier this month, the world’s finance ministers and central bankers congratulated each other on progress in curbing inflation and reviving post-pandemic economic growth. But they also acknowledged an excess of unfinished work — in particular, on improving financial stability, restoring fiscal discipline and fighting climate change.

Governments need to see that these tasks, each vital in its own right, are linked. Fiscal control is essential for financial stability, and better carbon-abatement policies can strengthen fiscal control. In a year of multiple elections, with more weight than usual given to empty promises and short-term calculations, getting this right won’t be easy. But the fact remains: These problems will most likely be solved together or not at all.

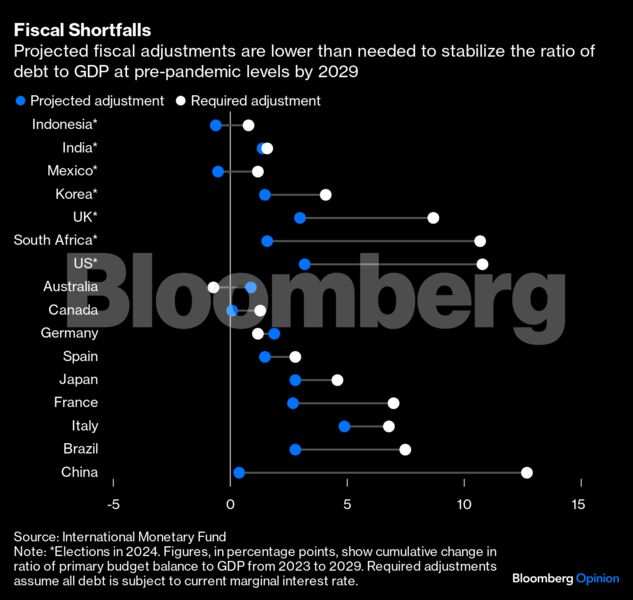

The pandemic drove public borrowing up almost everywhere. Governments spent heavily to cushion their economies as stalled output and employment reduced revenue. In much of the world, efforts to rein in the resulting surge of public debt have barely begun. Current policy is not yet on track to stabilize the ratio of debt to gross domestic product at its pre-pandemic level.

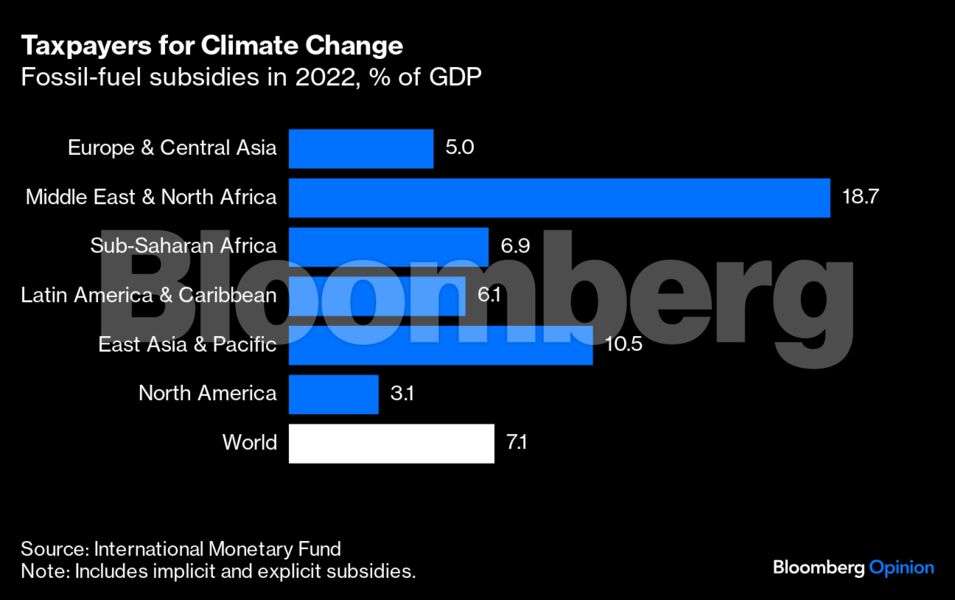

Higher debt makes economies more financially fragile, not just because it seeds doubt about a government’s ability to meet its obligations, but also because it limits the scope for new stimulus when the next big shock comes around. Granted, advanced economies like the US and most of the European Union have more leeway. For a while, they can get away with mounting debt because investors are slow to question their creditworthiness. That’s a luxury denied to many emerging-market economies, where the risks of fiscal and financial distress are more immediate.Climate change heightens these dangers. The transition to clean energy requires enormous public investment in electricity generation and distribution, in addition to the far larger expense of mitigating the damage caused by rising temperatures. Further delay will increase the public and private costs more quickly, while investing too little in the green transition is a woefully false economy.Equally important, smart reforms in taxation and government spending can accelerate this effort and promote short-term fiscal control at the same time. In many countries, fossil-fuel subsidies are still a major (and growing) public outlay. They amounted to a staggering $7 trillion in 2022, equivalent to roughly 7% of global output. These subsidies are partly explicit (in the form of payments to offset the cost of producing energy) and partly implicit (in the form of pricing systems that ignore environmental damage and fail to tax emissions appropriately). Taken together, they neutralize other efforts to curb emissions via regulation and other direct controls — and dig heavily indebted governments into an even deeper hole.

Fiscal prudence is especially urgent for poorer countries. As a proportion of GDP, emerging-market economies have lower environmental taxes and much higher fossil-fuel subsidies than advanced economies. If they dialed down their subsidies and raised more money through excise taxes on fossil fuels — a kind of revenue that’s relatively easy to collect — they’d discourage carbon emissions while improving their budgets and promoting financial stability.For rich and poor countries alike, pursuing all three goals at once is not just necessary, but a matter of hardheaded self-interest.