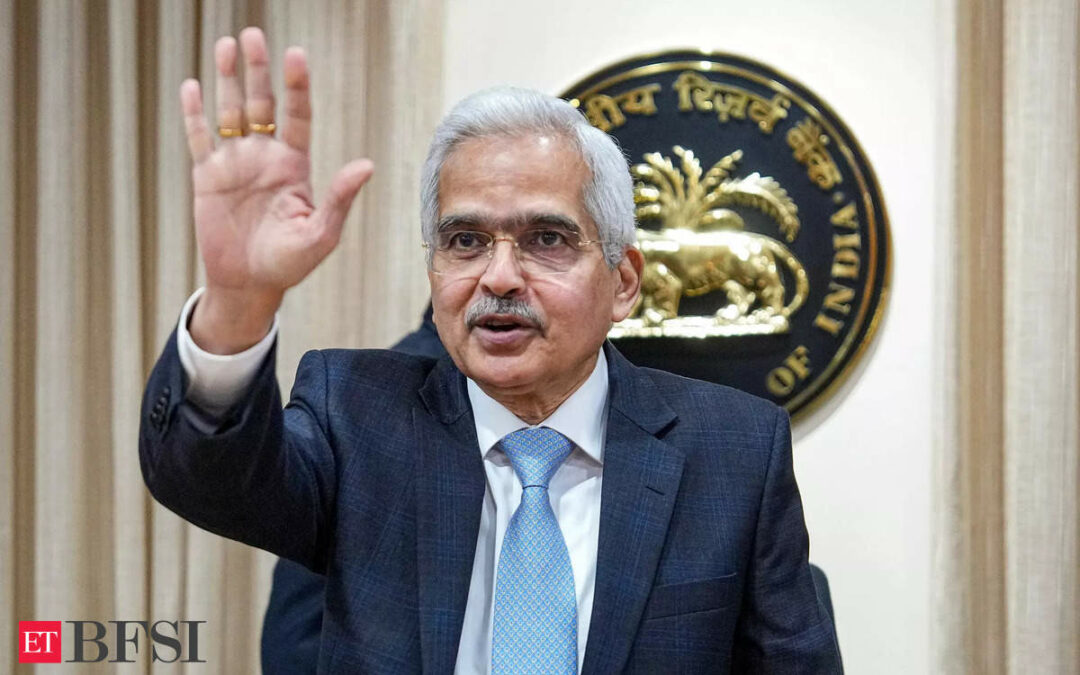

When Shaktikanta Das, the Governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), joined the central bank five years ago, he had waded into a government-RBI rift. A deft bureaucrat like his predecessors Duvvuri Subbarao and YV Reddy, Das had a tough job: to clean the mess left by high-profile economists Raghuram Rajan and Urjit Patel whose tenure at the helm of the RBI was marked by ugly spats with the government, erosion of confidence and high uncertainty.

When Das was named as the governor on 12 December 2018, Patel had resigned citing personal reasons, but many believed it was an outcome of the dispute over the transfer of surplus reserves to the government and liquidity for non-banking companies. Patel had resigned after months of bickering between the government and the RBI.

Das, a shrewd and able career bureaucrat, was a far cry from celebrity economist Rajan who cut a larger-than-life figure and got famous for saying, “My name is Raghuram Rajan, and I do what I do,”, or an academic Patel who would jealously guard the autonomy of the RBI. Das was supposed to heal the RBI-government ties and bring stability to a central bank that saw high turbulence under his two predecessors.

Many will say Das has been fairly successful in carrying out his brief at the RBI.

What Das brought to the RBI

Having worked equally at ease under three different finance ministers — P Chidambaram, Pranab Mukherjee and Arun Jaitley — Das, a seasoned financial bureaucrat, was seen as a bureaucrat who preferred to take a non-confrontational approach to problem-solving. Das had played an important role in the preparation of eight Union budgets — four as joint secretary and additional secretary in-charge of the crucial budget division and two each as revenue and department of economic affairs secretary.

Before he joined the RBI, Das had been a key link in several crucial economic decisions since he moved to the finance ministry in 2008. Be it GST — where he was part of the grand bargain on a five-year compensation plan for states and the amendment to the Constitution for rollout of the new regime — or tough negotiations with the Swiss government for information sharing on tax evaders, the Das emerged as a key troubleshooter, forging agreements. He was also responsible for drafting the Insolvency & Bankruptcy Code as well as drawing up the contours of the Fugitive Economic Offenders Bill and the law on black money stashed overseas. If Patel, his controversial predecessor at RBI, was the author of the MPC framework, Das was the man who implemented it, by working out amendments to the law as well as setting the inflation target.As the economic affairs secretary, Das was the key man behind the planning and execution of demonetisation drive. Most of the public statements on demonetisation had been made by him which led to the impression that the government was at the forefront of the drive instead of the RBI.

A 1980-batch IAS officer of Tamil Nadu cadre, Bhubneswar-born Das was also responsible for Tamil Nadu’s successful SEZs and industrial policy. He withstood political pressure to allot government land to private IT companies in Tamil Nadu without a bidding process. Das was seen as a cautious civil servant but he didn’t shy away from tough decisions such as dismantling the Foreign Investment Promotion Board to speed up clearances.

A challenging career

The first major challenge for Das was to bridge the differences that had widened between the central bank and the government while also upholding the credibility and autonomy of the central bank. Das, a consensus-maker, readily took to the job of normalising ties with the government and was successful at it. Das took a more conciliatory approach toward banking sector regulations compared to his predecessor. He met with bankers to hear their concerns about liquidity constraints in the economy, and gave more leeway to small and medium enterprises with regard to their loan repayments.

Experts saw a softer approach towards central bank regulatory supervision with the decision by the RBI to remove a number of public sector banks from the strict lending restrictions relatively soon after the Das’ appointment.

But Das was to face far bigger challenges ahead when he would be required to steer the economy through high turbulence: Covid lockdowns, supply chain crisis and the Russia-Ukraine war.

Barely a year after Das took charge as the RBI governor, Covid hit the world. As a key economic policymaker, Das faced challenging times in managing the disruptions caused by the lockdown. He chose to cut the policy repo rate to a historic low of 4 per cent, continuing with the low-interest rate regime for quite some time to help the economy hit badly by lockdowns. The GDP growth saw recovery due to the low-interest rate regime.

When Das was reappointed as the governor in 2021 for another three years. it was seen as an expression of confidence in his policies.

In May 2022, the RBI announced a surprise 40 basis point interest rate hike, the first in nearly four years as the Russia-Ukraine war triggered fears over over global inflation. The rates had reached a record 4 per cent low after the RBI under Das went on a rate-cutting spree after the pandemic struck in early 2020. The RBI hiked the repo rate by 250 bps points till April this year when it paused the rate-raising cycle. Das’ comment that the RBI keeps an Arjuna’s eye on inflation attracted much commentary on the impact of the RBI’s policy on the growth-inflation dynamic.

“It was in managing [the Covid] crisis that Das had perhaps his greatest impact, appearing as a voice of calm amid the fear, and steering the RBI deftly between intense political pressures on one side and economic disaster on the other,” noted Central Banking, the publication that gave Das the Governor of the Year award in March this year. In September, Das has received an A+ rating in the Global Finance Central Banker Report Cards 2023.

The fact that despite all the global shocks India has been able to achieve a high growth rate, rare among large economies, in this period while also having inflation moderate in comparison to other economies goes to show the success of Das-led RBI in ensuring macroeconomic stability in highly turbulent times. India has shined as an exception in the world when many big economies have been struggling with high inlfation and low growth.

Das brought humility to the RBI

Das had done a master’s degree in history from Delhi’s St Stephen’s College. Though he had played a key role in financial policy-making at the Centre for a long time, many had doubted Das’ ability to steer the central bank for his education in history instead of finance or economics as was the case with his two more illustrious predecessors. But Das has proved that a governor’s job is not as much about history or economics as about what it is purported to be: the governance.

Das is a man of measured language unlike his many predecessors who were given to express themselves freely and not often without dramatic effect. He knows the power of an RBI governor’s words whose one loose comment can move markets.

In comparison to his two predecessors during whose tenure the RBI-government ties deteriorated, Das is a humble man who doesn’t cut a larger-than-life figure. Last week at a press conference, Das told a junior staff to address him without the “honourable” prefix, and call him just “governor” instead. “I think in future, just ‘governor’ will be better than ‘honourable governor’,” he said. Das knows, and people have seen during his five years at the RBI, that it’s not as much the person as the role that matters.

(With inputs from TOI and agencies)