Today’s financial lesson: We can manage risk—but terrible stuff can still happen. This thought, of course, was prompted by my recent cancer diagnosis. But the notion is also all too relevant to money management.

But let’s start with health matters. In 1995, I began training for my first marathon, which I ran in May 1996 in Pittsburgh and finished in just under three hours. Ever since, I’ve been a bit of an exercise nut. Even today, I work out for an hour every morning and take a walk every afternoon.

Despite that, my cholesterol is a tad higher than it should be and I’m considered prediabetic, so I eat a high-fiber diet, and I strictly limit processed meats and fried foods. I also try to hold the line on vino, typically restricting myself to a single glass with dinner. These are the sort of health issues I’ve been focused on for years, and which I worried would come back to haunt me.

Instead, I got cancer.

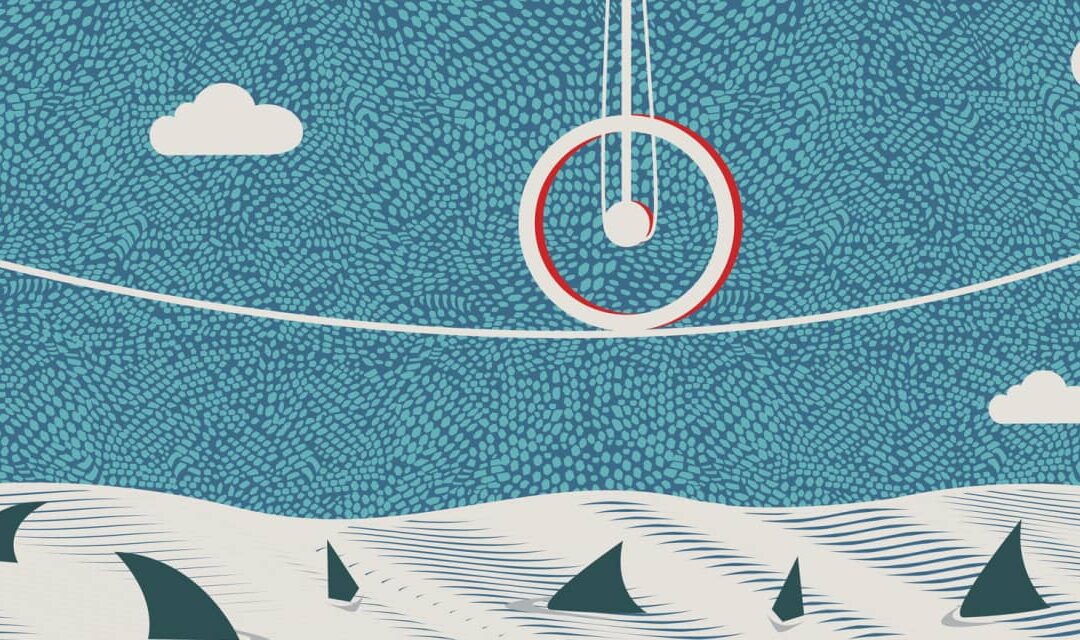

It strikes me that managing money isn’t so different. We’re laser-focused on certain risks. Stock market crashes. Auto accidents. Our home burning down. Big medical bills. Losing our job. Hefty home repairs. All this drives the size of our emergency fund, the insurance we carry, and the sum we allocate to bonds and cash investments. But what if the risks we’re trying to contain aren’t the risks we get hit with?

I’ve long argued that, to build wealth, we should avoid chasing investment performance and instead focus on three less-exciting endeavors: saving diligently, keeping a tight lid on investment and other costs, and managing risk. This three-part approach is at the core of the frugal index-fund investor’s playbook—one I’ve followed for decades—and it’s also good advice for the rest of our financial life.

To me, of these three dimensions, risk management is easily the most fascinating, but it’s also the trickiest. Consider:

- Limiting one risk can open us up to others—such as the cash-loving investors who fear stock market turmoil but end up getting decimated by inflation.

- Dangers arise that never even occurred to us. The 2020 pandemic is a classic example. But before that, there was 2008’s financial meltdown, the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the 1998 financial shockwave caused by the collapse of hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management. The lesson: Purportedly low-probability events seem to happen with surprising frequency.

- Some of our biggest financial hits come from an unlikely source: our own family. Think of the adult children who get themselves in financial trouble and need to be bailed out, the bitter divorce that enriches only the lawyers, or the elderly parents who gave no thought to their later years and suddenly need long-term care.

- The apparently mighty often collapse with shocking speed. Remember the rapid demise of Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, Enron and WorldCom? For many employees of these firms, the result was not only a lost job, but also a portfolio full of worthless shares.

- Folks often get into big trouble not because they purchase insurance that offers too little coverage, but because they completely neglect to buy certain policies. On that score, perhaps the two biggest oversights are disability coverage and umbrella-liability insurance.

- I view the long Japanese bear market as perhaps the seminal financial event of my lifetime. Could something similar happen in the U.S. or Europe? Probably not—but it is indeed a risk, one ignored by those whose home bias leads them to stick largely or entirely with their own nation’s stocks.

- If leverage is involved, our financial life can unravel fast. Consider the couple who own a few heavily mortgaged rental properties. The economy falls into a recession, their tenants get laid off and the rent checks stop coming in. Our landlord couple are left to cover the mortgage payments with their salaries, which is just about doable—until one of them also gets laid off.

It’s easy to dismiss layoffs, disability, pandemics and long bear markets as low-probability events. But spare a thought for Pascal’s Wager. As 17th century French philosopher Blaise Pascal saw it, it was logical to believe in God. If you believed and God didn’t exist, your religious devotion might cause you to miss out on a little earthly fun. But if God does exist and you don’t believe, the price is considerably higher: an eternity roasting in hell. In other words, we should focus less on the odds of something happening and more on the consequences.

I don’t want readers to obsess about risk. But I would encourage folks to build financially resilient lives and to avoid big assumptions about the future. Risk has now arrived for me, and it’s taken a form I never imagined. Fortunately, I’m well-prepared financially, thanks to health insurance and a plump nest egg.

But what if my fate instead had been, say, decades of dementia? Would my nest egg have held up?

I’m not sure there would be any way I could have reasonably prepared. Still, there’s an important lesson here: While we have only one past, we face all kinds of possible futures—and it’s worth asking whether there are futures we aren’t even considering.

This column originally appeared on Humble Dollar and was published with permission.