India’s central bank is clamping down on risky consumer lending as the economy booms, a move that’s likely to hurt banks but only have a limited impact on growth.

The Reserve Bank of India on Thursday told lenders to set aside more capital for unsecured consumer loans, such as credit cards and small, personal loans.

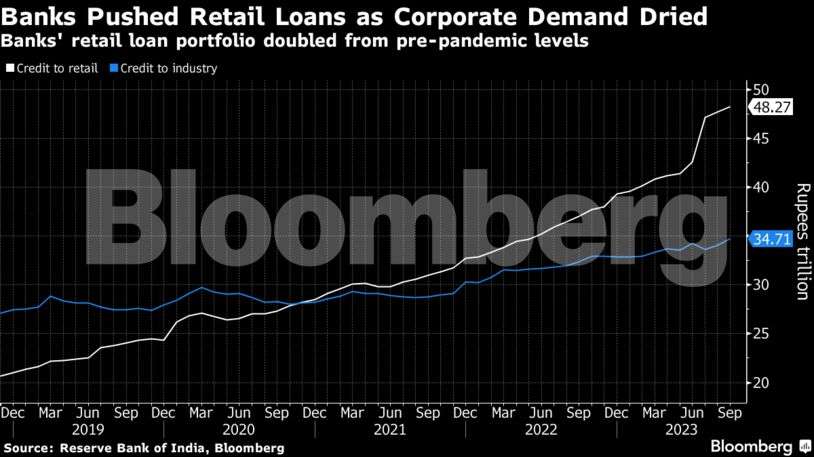

That type of borrowing had surged more than 25% in the past year, according to Macquarie Group, far higher than growth in consumer incomes, potentially creating a debt trap for borrowers and giving rise to defaults.

The RBI’s measures prompted a selloff in bank stocks on Friday, with analysts saying a rise in borrowing costs will hit profits. The NSE Nifty Bank Index and S&P BSE Financial Services fell 1.5% and 0.8% respectively.

For the broader economy though, the impact may be more muted, economists said. The RBI’s restrictions don’t apply to loans for housing, cars and other secured borrowing, which makes up more than three-quarters of retail loans.

“This is more a macro-prudential step aimed at making unsecured lending costlier,” said Gaurav Kapur, an economist with IndusInd Bank Ltd. “Demand will be hit, but the impact on overall consumption will be fairly limited.”

Policymakers are trying to strike a balance between growth in the fastest-expanding major economy in the world, and financial stability. They’re worried that some consumers are taking out more short-term loans to buy phones and TVs than they can afford, and banks will soon be saddled with bad debt.

While unsecured lending has grown more than 20% in the past year, the average monthly income of urban residents in India has increased only 7.5% in nine months to June, according to ICICI Securities Ltd.

Governor Shaktikanta Das and other senior RBI officials had been raising the alarm bell for months already, telling lenders to build up their protection against risks.

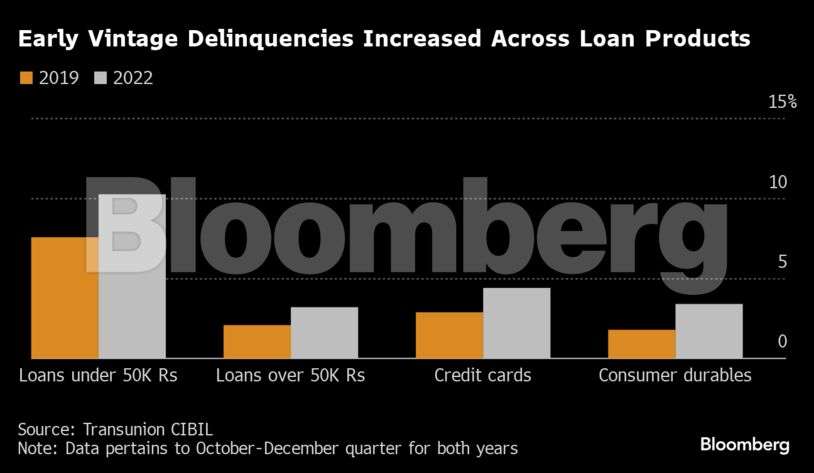

Of particular concern to the regulator are loans for small ticket items of up to 50,000 rupees ($600), which has seen a pickup in bad debt. According to data from Credit Information Bureau of India Ltd., India’s largest credit bureau, non-performing assets in this segment increased to 5.4% of total loans by June, from 4.2% a year ago.

Credit card spending hit a record 1.48 trillion rupees in August ahead of India’s months-long festival period, when consumers splurge on everything from household goods, clothes and food. Consumption makes up about 60% of India’s $3.3 trillion economy, with households more credit dependent now than before the pandemic.

Impact on Banks

The RBI’s measures will increase lending rates, reduce the capital adequacy ratios for some banks and likely hit their profits, according to S&P Global Ratings.

“Slower loan growth and an increased emphasis on risk management will likely support asset quality in the Indian banking system,” S&P’s credit analyst Geeta Chugh wrote in a note. However, Tier-1 capital adequacy of banks will decline by about 60 basis points, according to S&P.

The RBI’s restrictions are particularly severe for India’s shadow banks and financial technology firms, which aren’t supervised as closely as banks. In the past four years until March, the personal loan portfolio of non-bank firms grew at a compounded annual rate of 30%, according to RBI data.

The RBI, which is also the banking regulator, has been tightening controls over non-bank financial companies, or NBFCs, in recent years, slowly aligning them with stricter regulations that apply to banks.

Top lenders including State Bank of India and ICICI Bank Ltd. have previously downplayed concerns about their personal loan portfolios, saying they were well protected against any possible financial risks.

Virat Diwanji, group president and head of consumer banking at Kotak Mahindra Bank, said Friday “it is safe to assume that the lending rates can go up anywhere between 40 to 75 basis points, but the actual scenario will be market-driven.”

A State Bank of India official said in response to queries that the bank’s capital needs will go up 55 to 60 basis points after the new rules. He said the bank would not be impacted in its ability to grow.

The worst hit could be digital lending platforms that depend on banks for their loans.

“Raising equity is going to be tough,” said Srinath Sridharan, an adviser to fintech firms. “For unlisted NBFCs and smaller players, private equity and venture are an option, but listed banks and NBFCs have restrictions so they are compelled to raise fresh equity from now on.”