The overhaul of the capital gains tax framework in the recent Budget has upset many. Equity investors are fretting that they must now shell out more tax on their gains. Real estate owners are livid that indexation benefits will be taken away. Taxpayers still holding on to the older tax regime feel ignored. Some of these tax changes may seem harsh now, but there’s a silver lining in this upheaval. For the first time, different assets are set to be brought on an even footing for taxation. This parity in taxes presents an opportunity for investors to finally let go of tax-led asset biases. It could allow investment merit, not tax efficiency, to guide asset choice. The portfolio outcomes may fare better now. Let’s understand how.

Tax sops lead to bad choices

For the longest time, our investment choices have been distorted by tax considerations. Our innate obsession with tax avoidance, accentuated by the disparity in tax rates across asset classes, have been the culprits. Certain asset classes benefitted from benign taxation compared to others. Indexation benefits were available for a select few assets. Further, taxes varied for products within a single asset class. For instance, domestic equities got preferential tax treatment over foreign equities. Debt funds were taxed favourably compared to bank fixed deposits, and so on.It fed biases towards specific assets among investors, who often ignored the suitability of individual assets. Abhijit Bhave, MD and CEO, Equirus Wealth, points out, “Investors have been swayed by tax-saving instruments and benefits, sometimes at the expense of the underlying investment merit.” This is because it is easier for investors to visualise the tax impact than the returns on an asset class, asserts Sandeep Jethwani, Co-founder, Dezerv.

There are downsides to this tax jugglery though. Experts say tax-driven investment choices ultimately leave the investor vulnerable. Most end up with an asset mix that is out of sync with their own risk tolerance and doesn’t suit their long-term goals. Bhave argues, “Prioritising tax optimisation over investment merit can lead to suboptimal investment portfolios as investors might end up with over-concentration in certain asset classes that offer tax benefits, but do not align with their expectation of returns based on financial goals and risk tolerance.” Jethwani points to 2009-10, when multiple issuances of tax-free bonds by public sector companies led to a very heavy allocation from investors to that asset class. “To a certain extent, this money got locked in tax-free bonds while the markets went up. Investors missed out on this opportunity,” he recalls.

The removal of indexation benefit from debt funds last year also sent investors on a wayward path. Shantanu Bhargava, Managing Director, Head of Discretionary Investment Services, Waterfield Advisors, remarks, “We have observed that in the past 15 months, a large swathe of investors has made tax-driven portfolio allocations. They have allocated to riskier products due to changes in taxation of vanilla debt mutual funds, possibly without carefully assessing and understanding the risks (market/credit) they have assumed in their portfolios.”

Besides, many tax-driven investments often suck out liquidity from the portfolio. “Prioritising tax savings can result in missed opportunities for higher returns, as well as a mismatch in cash flow due to products with longer lock-in periods,” avers Bhave. Every year, individuals are lured into buying high-premium traditional insurance plans, convinced that it is a good way to save tax and build assets. Only later do they realise that they have been locked into paying hefty premiums for several years, for a payoff that cannot even beat inflation. The utility of traditional insurance policies, beyond the tax savings these offer, is dubious. Escaping this money pit is not possible without surrendering the policy at a substantial loss.

Similarly, many continue to accumulate real estate, encouraged by the tax concessions on buying as well as the favourable taxation on selling. Often, however, these burden the savings, leaving one with an illiquid asset when the need arises. Vipul Bhowar, Director, Listed Investments, Waterfield Advisors, says, “Focusing solely on tax optimisation can hinder an investor’s ability to adapt to market changes, overlook high-potential investments, ultimately stunting portfolio growth and wealth accumulation.”

Now, parity in taxes for different assets

Investors can pick assets purely on merit rather than to optimise their tax outgo.

Tax parity has levelled the investing ground

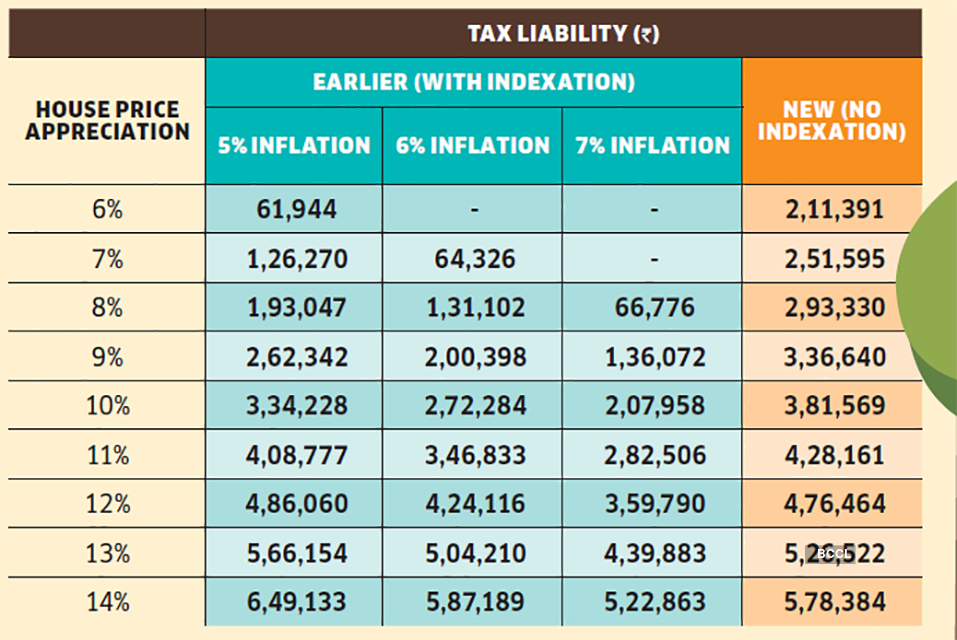

‘Tax optimisation’ might soon become a thing of the past. Now, nearly all assets will be taxed at the same rate. Long-term capital gains across the listed and unlisted space will now be taxed at a standard rate of 12.5%, which will do away with the differential tax rates of 10% and 20% for various assets. So, domestic equities, gold and international funds, real estate and listed bonds will now attract 12.5% tax on long-term gains. The only differing factor remains the qualifying holding period as a longterm asset. This has also been narrowed to 12 months and 24 months for certain assets.

Experts insist that this paves the way for simplifying investment choices. Varun Fatehpuria, Founder and CEO, Daulat Wealth Management, says, “The new tax regime has simplified the overall taxation structure across different asset classes. Going forward, investors should evaluate asset classes on their individual merit and decide how these fit into their overall portfolio.” Bhowar adds, “Through the simplification of tax framework and establishment of uniformity across asset categories, the new regime affords investors the opportunity to direct their attention to the fundamental attributes of their investments.”

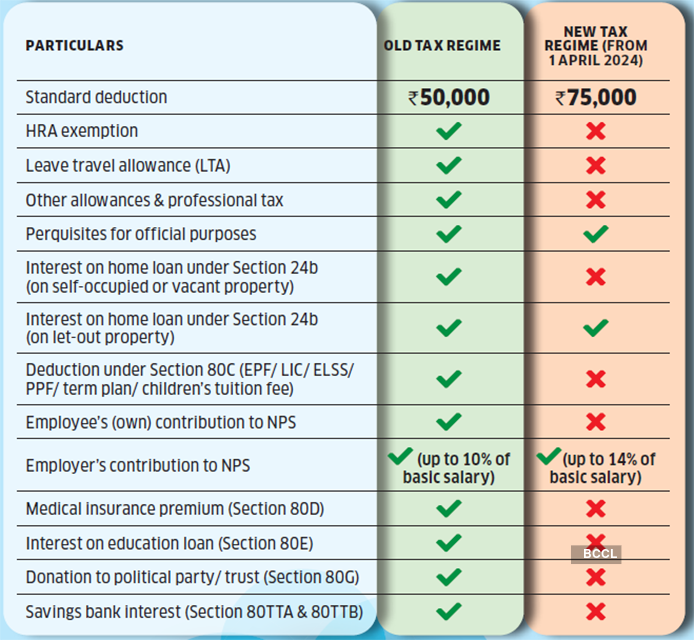

Some of the tax tweaks have taken away previous anomalies. For instance, the Budget has brought LTCG tax rate on gold funds, international funds and domestic fund of funds (FoF) on a par with equities. After the change in last year’s Budget, these funds were being treated as debt funds from the taxation perspective, where gains were taxed at the slab rate regardless of the investor’s holding period. This unfavourable tax treatment discouraged many from taking this route. “In the move to bring taxation on debt funds on a par with bank FDs, collateral damage was suffered by other funds,” says Juzer Gabajiwala, Director, Ventura Securities. Now, these will be taxed at 12.5% after being held for more than 24 months.

This tax rationalisation has not been restricted to the recent Budget. The government has gradually been ushering in an equitable tax system over the past few years. Bhargava remarks, “The government has clearly been moving towards simplifying the income tax system for some time, and the finance minister has made significant progress in this regard in this Budget.” In 2018, it reintroduced long-term capital gains tax on equities, which had enjoyed zero tax for many years. It provided small relief by allowing gains up to Rs.1 lakh to be tax-exempt in a financial year. Last year, it made another big tax change in debt funds, which had enjoyed favourable taxation compared to bank fixed deposits. Any gains realised after three years were taxed at 20% after indexation, which helped reduce the tax liability. With debt funds now taxed at the investor’s tax slab, the tax arbitrage has been taken out of the equation. The playing field has been levelled. Along similar lines, the introduction of the new, simplified tax regime has done away with the vexing web of deductions and exemptions that defines the old tax regime. It has already nudged investors to let go of certain suboptimal investments.

New regime has simplified tax filing

It has replaced deductions and exemptions with lower tax rates

Nearly 72% of the 7.28 crore taxpayers who filed their returns for the assessment year 2024-25 have opted for the default new tax regime.

Focus on portfolio, not tax

It is never a good idea to base investing decisions on tax savings alone, say experts. Fatehpuria exhorts, “We continue to advocate focusing on asset allocation, not picking investments based on taxation structure. Tax is incidental.” He suggests looking at tax optimisation within the same asset class (debt funds versus FDs) rather than switching to an asset class with a relatively favourable taxation. Bhargava says, “Everything is fine in moderation, and we are confident that innovative products have a role to play in well-diversified portfolios. However, we continue to believe that portfolios should be tax-informed, not tax-driven.”

It’s time investors aligned investments with their goals rather than tax incentives. Don’t stash money in low-return, illiquid or risky assets just to save tax. “With a level playing field, investors can focus on the intrinsic risk-reward profile of investment options in alignment with their financial goals and risk-taking ability,” asserts Bhave. “They should focus on building robust portfolios aligned with their financial aspirations, rather than chasing tax deductions,” exhorts Bhowar.

While the recent tax changes in certain assets may put off investors for now, these could prod them to assess a product more objectively. For instance, investors can now look at the investment proposition of debt funds on their own merit. “Investors in debt funds earlier missed out certain nuances, ending up taking credit risk and interest rate risk,” points out Gabajiwala. Despite having their tax benefit taken away, debt funds retain some advantages. These will let you defer tax liability until redemption. Interest income accrued from a bank FD is taxable every year even if it is paid out at maturity. Losses, if any, from debt funds can be carried forward to be set off against gains in subsequent years.

Gold and international funds are no longer a tax drag

Returns from these categories saw collateral damage after last year’s tax changes.

* For investment made on or after 1 Apr 2023 and redemption before 23 Jul 2024. ** For investment made on or after 1 Apr 2023 and redemption on or after 23 Jul 2024.

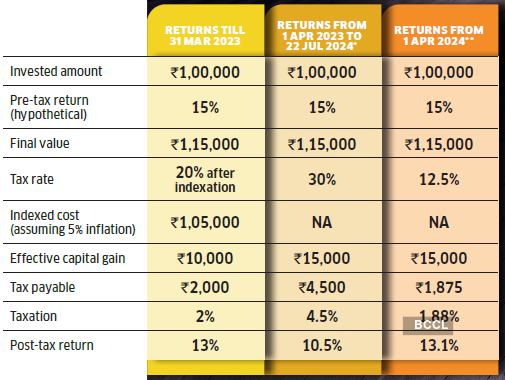

Property owners won’t be insulated from inflation

For revised lower tax rate to be beneficial, price appreciation in asset must exceed 11% in many cases.

The above illustration assumes original house cost as Rs.50 lakh and sale after 5 years.

For property bought before 23 July 2024, investors have the choice of paying lower of the two options: LTCG tax at 12.5% without indexation, or 20% with indexation.

Likewise, for property owners, the removal of indexation may seem unfair, which was evident from the backlash after the Budget. It was enough to force the government to offer a reprieve to owners who had bought property before 23 July this year—they now have the option to pay tax at the new lower rate of 12.5% or opt for 20% tax rate with indexation when they sell property. For those buying property after 23 July, the indexation option is gone and property sellers are no longer insulated from the impact of inflation. It could lead to higher taxable gains and liability. Experts reckon it is not such a bad thing over the long term. Property owners will now have to recalibrate. For the lower tax to be beneficial, the asset must earn a superior return. Our calculations suggest the property must fetch in excess of 11% return to incur lower tax liability under the new rate. Investors must now objectively assess if their purchase can deliver the requisite return. Confronted with the new reality, it may nudge speculators towards better asset choices. “Instead of making decisions based solely on short-term tax benefits, focus on building a portfolio that can generate enduring wealth,” contends Bhowar.

Some tax changes will make certain assets more appealing. For instance, investors can now reintegrate international funds and domestic FoFs as core investments without worrying about higher taxability. There are reasons that make foreign equity investments compelling regardless of tax considerations, insists Suresh Sadagopan, Founder, Ladder7 Financial Advisories. “You get an exposure to a different economy with characteristics and market segments that are not available in the domestic market. It offers geographical as well as currency diversification benefits.” Similarly, last year’s tax hit on gold funds created a disconnect with SGBs, which are tax-exempt on maturity. With the tax rate revised to 12.5%, the tax gap is not as glaring, making gold funds competitive. Investors need not lock into SGBs for eight years simply for tax exemption.