Summary

- We share the near-universally held view that the FOMC will leave the fed funds rate and pace of quantitative tightening (QT) unchanged at the conclusion of its upcoming meeting on January 31.

- The FOMC’s decision last month to leave the fed funds rate unchanged for a third consecutive meeting made it increasingly clear that the most aggressive tightening cycle since the 1980s has come to an end. Consequentially, overall financial conditions have eased considerably since the last policy meeting.

- We also look for the FOMC to remain in a holding pattern in terms of its policy guidance, and we expect only minor changes to the post-meeting statement relative to December. A change to the statement we would not be surprised to see at this meeting is the removal of the paragraph on the U.S. banking system and financial conditions.

- Overall, we view this meeting as one where the Committee will buy time to discern if inflation is indeed on a sustainable path back to 2% and serve as an opportunity to build consensus around the conditions for eventual policy easing.

- Market chatter about changes to the existing pace of QT has picked up recently, and we expect the meeting will include a discussion about the path forward for the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet.

- Our base case is that the FOMC will announce a plan to slow the pace of QT at its June meeting, although we would not be shocked if the Committee decided to do so one meeting earlier in May.

- Specifically, we expect the runoff caps for Treasury securities to be reduced to $30 billion while MBS caps are dropped to $20 billion starting on July 1. We anticipate this slower pace of QT running until year-end 2024. Under this scenario, the Fed’s balance sheet would reach a trough of $6.8 trillion or so at year-end 2024 and begin growing gradually again thereafter.

The Less Said the Better?

We share the near-universally held view that the FOMC will leave the fed funds rate and pace of quantitative tightening (QT) unchanged at the conclusion of its upcoming meeting on January 31. The FOMC’s decision last month to leave the fed funds rate unchanged for a third consecutive meeting made it increasingly clear that the most aggressive tightening cycle since the 1980s has come to an end. The December post-meeting statement continued to signal that, in the near term, any adjustment to the policy rate is still more likely to be up than down. However, a small tweak sent a big signal that the Committee believes additional tightening is increasingly less likely. Specifically, the insertion of “any” to the sentence “In determining the extent of any additional policy firming that may be appropriate…” indicated that the Committee is more confident that the current policy setting is sufficient to return inflation to 2% on a sustained basis.

Moreover, in the post-meeting press conference, Chair Powell underscored the Committee’s shifting focus away from potential further hikes and toward eventual policy easing. Not only did the FOMC continue to discuss how long the fed funds rate may need to remain restrictive, but the Committee discussed when it may be appropriate to remove current policy restraint—a discussion that is the first step on the road to eventually easing.

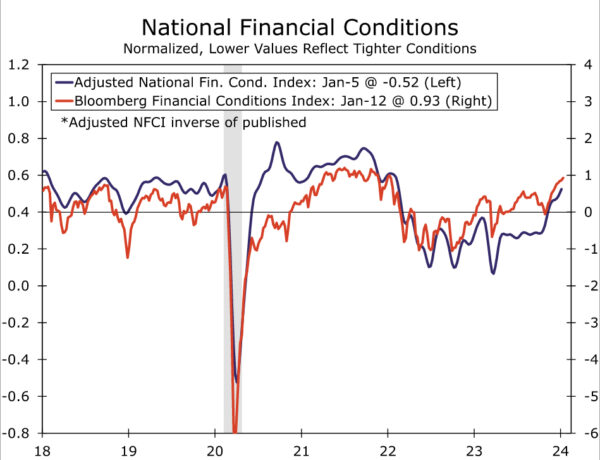

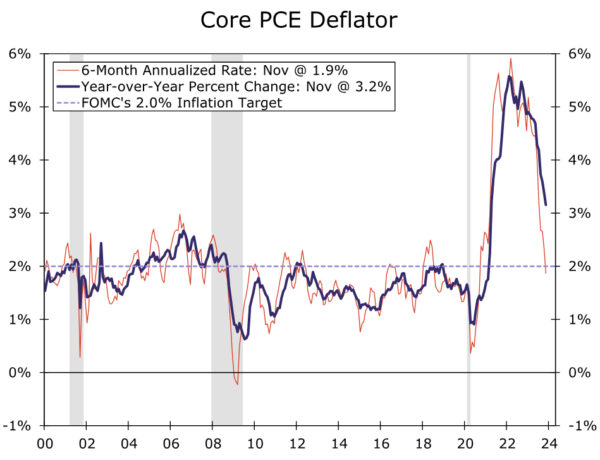

With Powell sharing that the topic of rate cuts had been broached, financial conditions loosened further over the inter-meeting period. At present, indices of financial conditions are sitting near the most accommodative levels since the FOMC began its current tightening cycle (Figure 1). That easing in financial conditions has caused some consternation about premature policy easing given that they are the channel through which the Fed’s policy settings impact the real economy. Inflation has fallen sharply in recent months (Figure 2), with the rise in the core PCE deflator slowing to a six-month annualized rate of 2.0% through December by our estimates. However, Chair Powell and other FOMC members have indicated they need to see progress continue in the coming months to be convinced inflation can return to 2% for the long-haul. Meanwhile, economic growth continues to hold up well. Employment increased more than expected in December, the unemployment rate remained unchanged at 3.7% and layoffs remain near record lows. GDP in the final quarter of the year looks to have risen close to a trend-like 2% annualized rate.

Therefore, we look for the FOMC to remain in a holding pattern, not only with the fed funds rate at its January meeting, but also with its policy guidance. While progress in lowering inflation over the past six months has built the case that rate cuts are coming, the economy’s recent performance suggests no imminent need to ease. Given a still-elevated degree of uncertainty over the outlook and a desire to limit further near-term easing in financial conditions, we suspect that Fed policymakers will want to be careful about sounding too dovish in the post-meeting statement and Chair Powell’s press conference.

As a result, we expect the post-meeting statement to include only a few changes from December. Guidance around the future path of policy likely will remain unchanged after the last meeting’s adjustment. Rather, changes are more likely to be in the characterization of recent economic activity.

On the less consequential side, the statement likely will remove the reference to Q3 GDP and acknowledge that growth in Q4 was solid, albeit slower than in the third quarter. (Preliminary data for Q4-23 GDP are scheduled for release on January 25.) We expect the statement will continue to note that “job gains have moderated” but “remain strong.” More consequential would be a change to the statement’s description of inflation. If the FOMC wants to clearly signal it is inching closer to eventual rate cuts, it could remove the reference to inflation remaining “elevated,” and instead say something along the lines of “Inflation has eased over the past year, but a sustained moderation in inflation pressures has yet to be convincingly demonstrated” (our emphasis on the possible new language).

One other change to the statement we would not be surprised to see is the removal of the paragraph on the U.S. banking system and financial conditions. The FOMC’s emphasis on the soundness and resiliency of the overall banking system came in the immediate wake of a handful of high-profile bank failures last March. But with the immediate crisis since passed and some policy easing on the horizon, its purpose has been served. At the same time, the easing in financial conditions since the autumn leaves the reference to “Tighter financial and credit conditions…” feeling stale. We believe the removal of this paragraph should be viewed as a tidying up of the statement, rather than a meaningful change in the FOMC’s thinking.

Overall, we view this meeting as one where the Committee will buy time to discern if inflation is indeed on a sustainable path back to 2% and serve as an opportunity to build consensus around the conditions for eventual policy easing. Our current view is that the first “normalization cut” will occur at the May 1 meeting.

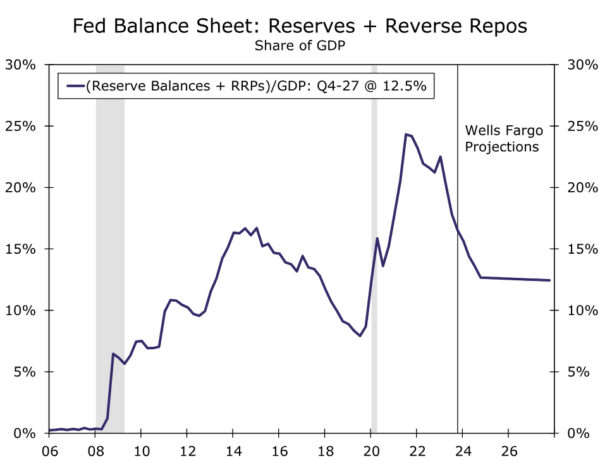

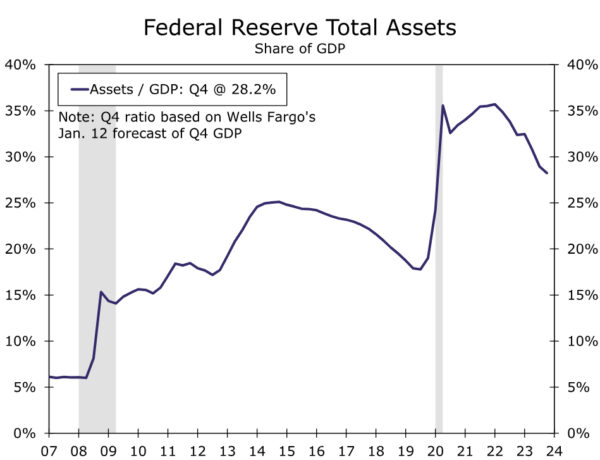

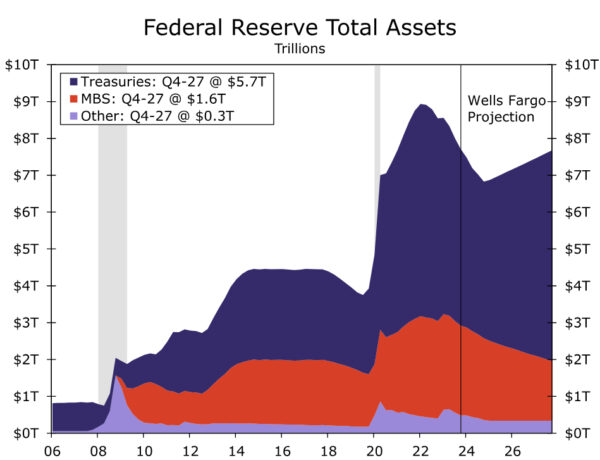

Time To Talk About QT

We suspect the January FOMC meeting will include a discussion about the path forward for the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet. The Federal Reserve has been shrinking its balance sheet since June 2022 in a process frequently referred to as “quantitative tightening” (QT). Starting in June 2022, the FOMC began allowing a maximum of $30 billion of Treasury securities and $17.5 billion of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) per month to roll off its balance sheet. These caps were increased to $60 billion and $35 billion, respectively, in September 2022, and they have subsequently remained unchanged. At present, the Fed’s balance sheet totals roughly $7.7 trillion, down from nearly $9 trillion at its peak in Q2-2022. That said, the Fed’s balance sheet remains significantly larger than its pre-pandemic size, both in dollar terms and as a share of GDP (Figure 3).

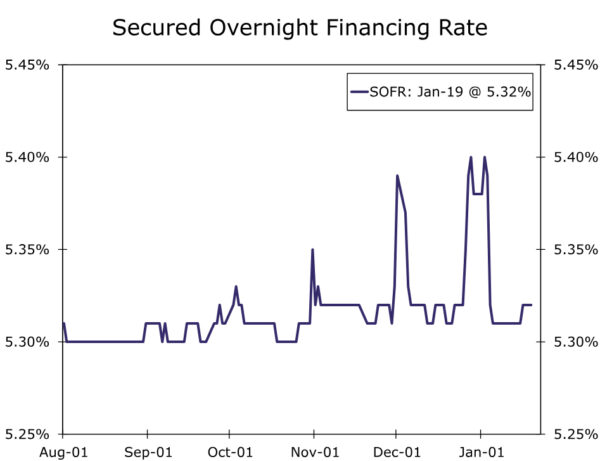

Market chatter about changes to the existing pace of QT has picked recently up for a few reasons. Money market rates have drifted higher around month-end over the past couple of months. For example, the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) increased by 8-9 bps for a few days around the end of November and again at the end of December (Figure 4). These moves proved temporary and receded shortly after month-end, and they were smaller than the similar month-end moves that occurred in 2018-2019 when the Federal Reserve was last undertaking QT. However, these small stresses are an early sign that liquidity may not be as abundant as it has been over the past few years.

Some Fed officials appear to have taken notice. In the minutes from the December FOMC meeting, “[several] participants suggested that it would be appropriate for the Committee to begin to discuss the technical factors that would guide a decision to slow the pace of runoff.” A speech from Dallas Fed President Lorie Logan on January 6 added more fuel to the speculation. In a previous role, Logan was manager of the System Open Market Account for the FOMC, and her expertise earned while managing the Federal Reserve’s securities portfolio means that many market participants put additional weight on her views in this area. Logan acknowledged that the “emergence of typical month-end pressures suggests we’re no longer in a regime where liquidity is super abundant and always in excess supply for everyone.” Logan suggested that it is “appropriate to consider the parameters that will guide a decision to slow the runoff of our assets.”

Our expectation is that the FOMC will spend the next few policy meetings discussing the path forward for the balance sheet. Our base case is that the FOMC will announce a plan to slow the pace of QT at its June meeting, although we would not be shocked if the Committee decided to do so one meeting earlier in May. Specifically, we expect the runoff caps for Treasury securities to be reduced to $30 billion while MBS caps are dropped to $20 billion starting on July 1. We anticipate this slower pace of QT running until year-end 2024. Starting in 2025, we look for balance sheet growth to resume to accommodate organic growth in liabilities (e.g., paper currency and bank reserves). We expect the FOMC will continue to passively reduce its MBS holdings in 2025 and beyond while replacing these MBS with Treasury securities, a move that would replicate what occurred in 2019.

If realized, the Fed’s balance sheet would reach a trough of $6.8 trillion or so at year-end 2024 and begin growing gradually again thereafter (Figure 5). The nadir in the Fed’s balance sheet would be only a bit higher than the $6.5 trillion projection in our “middle-of-the-road” scenario outlined in our report on QT from last October. QT that slows/stops modestly sooner than expected would not have a major impact on our expectations for the level of rates and the shape of the yield curve. In this scenario, we look for RRP balances to decline to about $200 billion by year-end, with bank reserves that are around $3.1 trillion at the trough. As a share of GDP, this would represent a meaningful liquidity buffer relative to pre-pandemic levels (Figure 6).