As the spectre of Houthi attacks engulf the Red Sea region, its repercussions on global trade are tightening the choke on Indian exporters. Freight rates have risen 600%, insurance costs are higher and container shortage is becoming acute. SMEs, already worried that their goods may not reach the buyers, are feeling the pinch of these factors as well.Vikas Singh Chauhan, Director of the Home Textile Exporters Welfare Association, points out that Europe freight that was $400-600 per container before the crisis has now rocketed to $4,000-6,000. “70-80% of exports in home textiles have been impacted,” he says, explaining that the rise in transportation and insurance costs is squeezing the working capital cycle and eating away the profits of traders.

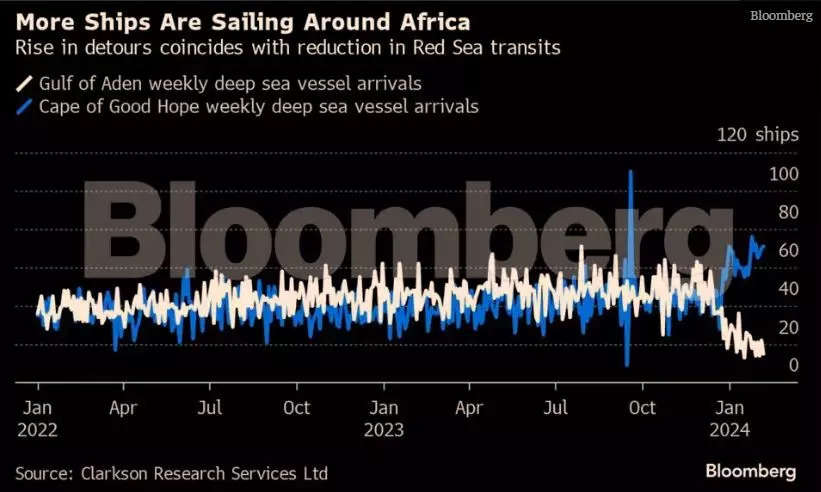

Indian businesses cannot avoid the Red Sea as it is a crucial trade channel linking Europe, Asia and the Middle East as it is the gateway to the Suez Canal: nearly 12% of global commerce and a third of the world’s container ship traffic pass through this region. The surge in attacks by Iran-backed Houthis on ships on this route has forced commercial vessels to divert to the longer route around Africa — around the Cape of Good Hope. This bottleneck has inflated expenses across the board — from freight rates and insurance premiums to container leasing spot rates. It also raises voyage distance by 40%.

Shipping companies have increased by threefold the prices they charge to transport a container from Asia to Europe as they circumvent the Houthi menace by navigating an additional 4,000 miles around Africa. They say the detour results in extra fuel consumption, higher operational and manpower costs, and adds over two weeks to the travel time in each direction.

Shipments are at sea

Chauhan explains that it has become a logistical nightmare. His shipments to Israel’s Port of Ashdod now reach in 83-120 days against 12 days previously. Freight rates to UAE have risen from $50-100 to $700-900, says Chauhan.

These shipments, with multiple transshipments, face a 600% increase in freight rates as shippers find it viable to reroute less-than-container load (LCL) — one of the two main categories of containerised transportation services popular among Indian traders — to Singapore and Egypt. This is putting pressure on Singapore port.

The port is also a bunkering (refuelling) point, points out Vijay Kalantri, Chairman of MVIRDC WTC Mumbai. With vessel traffic increasing in Singapore, shipping lines are also struggling to find alternative locations for bunkering.

Kalantri says the surcharge on 40-foot containers on the Red Sea route is $3,000. This is a new charge.

A report by UK-based Altana, which gives supply chain insights to governments, recently said the Red Sea disruption is affecting 79% of Europe’s apparel imports from Asia. Chauhan concurs with this finding, saying the additional manoeuvring on seas has impacted 70-80% of exports by volume and 20-30% in value in the home textiles sector. Not many people are forthcoming in acknowledging such a steep fall in numbers, he says.

Some destinations remain relatively insulated from the Red Sea effect, like New Zealand and Australia. But consignments to these geographies go via Singapore, which is seeing vessel congestion and connectivity issues that are raising transit times. Also, most textile exports from India go to Europe, the US, and West Asia, making the Red Sea unavoidable for traders looking to send goods more cheaply and quickly.

Cost of the impact

Freight spot rates are spiking as shipping companies are factoring in the additional costs of going around the Cape of Good Hope or factoring in the additional risk premium of using the Red Sea route, says Jitendra Popat, National Head of Sea Freight at Jeena & Company.

A 40-foot container that used to cost $500 started costing $1,000 on December 20; $2,150 on January 1 and $3,600-4,400 from January 16, he explains. “Freight rates increased 700% to 850% in a short span of 1.5 months.”

The problem is more acute for companies relying on goods that have to reach a destination within a time limit. These companies cannot wait longer for a rerouted ship to arrive without taking a hit on their financials.

According to Ranjith Raja, Head of EMEA Oil Research at LSEG (London Stock Exchange Group), the Red Sea crisis is primarily responsible for the current sharp spike in spot rates. This is mainly because vessels being locked in on their current voyages for a longer period reduces the available tonnage in the market for chartering. This results in a shortage of supply that results in a spike in spot rates.

Shipments from India to Europe, North America and South America see a cumulative delay of 14-21 days because of a 7-day rerouting, says Chandrachur Datta, Partner at Vector Consulting Group. “This results in a shortage of supply, compelling pharmaceutical companies to opt for costly air freight, impacting their financial health.”

However, the turbulence has made air routes also unviable for industry. Nishant Parmar, Regional General Manager of Delhi-based Blue Bird Cargo Pvt Ltd, says air freight costs have doubled, and there is no space on planes taking goods to destinations in Europe and the USA.

Paris-based Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimates the tensions to cause a 5% increase in import costs for its members, leading to a notable increase in inflation. Nikkhil K Masurkar, CEO of Entod Pharmaceuticals, says the crisis is feeding itself as disruptions in shipping lanes and delays in cargo deliveries are causing shortage of vessel availability and driving up spot rates. “While the extent of the crisis on spot rates may vary depending on various factors, including the duration and severity of the crisis, it remains a significant factor influencing shipping costs and supply chain dynamics in the region and beyond,” Masurkar adds.

Insurance & inventory pangs

Industry players say there has been a significant surge in marine war risk premiums, increasing by approximately fifty times compared to before the war. “We have to shell out extra, exceedingly extra than what we used to pay,” says Jitendra Srivastava, CEO of Triton Logistics & Maritime Pvt Ltd.

“Insurance costs are definitely up — to the tune of 25-100% depending on the nature of the cargo. In some time-sensitive product ranges (pharma, seafood, agri commodities, etc), it is above 200% of the value of the goods. Facing a barrage of drone and rocket attacks, insurance companies are quite hesitant to provide cover to goods. That major trade route has suddenly turned economically unviable for them, and companies who are still risking it are charging huge war risk premiums (WRP). In sum, insurance companies are exploiting our situation.”

Insurance costs depend on factors such as vessel type and age, cargo, sailing history, risk perception and security concerns. Speaking on condition of anonymity, an official of a London-based financial information company says the common insurance premium rate before the Red Sea crisis started was 0.05-0.7%. But it has now reached almost 1% of the value of the asset.

To make matters worse for the industry, there seems to be no sign of immediate relief for the sector. Japanese shipping giant Mitsui OSK Lines estimates tensions in the Red Sea to disrupt the trade route for a year.

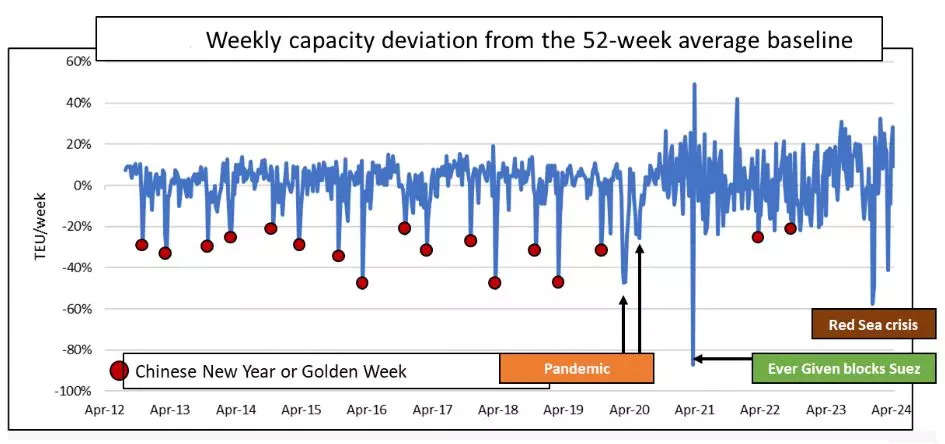

The severity of the problem has made traders draw parallels with the supply chain crisis of 2020 — seen during the Covid lockdowns. Businesses have not forgotten the detrimental effect of that, and some are yet to return to normalcy after that hit. Experts have predicted that it might take years for supply chains to recover and return to the pre-pandemic levels of efficiency.

They fear a new problem: inventory bloating, which happens when fear of supply disruptions force companies to place additional orders, to add buffer stocks, leading to higher storage costs. This comes with its own risk. Recently, retailers in the US and Europe were struggling to clear stocks as their additional inventory, ordered to buffer them from Covid disruptions, were not moving off the shelves due to a dip in the economy.

Industry players say overseas buyers are taking time to commit to any deals as they want to know how the situation will unfold. They are asking Indian suppliers for deeper discounts or hold shipments. This has squeezed the working capital cycle of several traders, particularly MSME exporters.

Container shortage, again

Heightened shipping costs are also affecting the availability of containers — an issue that had crippled trade during the pandemic. The Drewry World Container Index, a key benchmark for container freight rates, has more than doubled since the previous year’s end. This reflects an acute shortage of containers.

Research by online platform for container logistics, Container xChange, shows the top 10 locations in container trading experiencing substantial month-on-month percentage increases in container trading prices. The highest container trading prices globally are in Chennai as compared with Nhava Sheva and Mundra in January ($1,546 in Chennai, $1,345 in Mundra, and $1,492 in Nhava Sheva). As an example of how leasing rates have reacted to the Red Sea crisis and its repercussions, Container xChange observes that certain stretches, like the Shanghai to Chennai route, have seen a substantial 144% rise in leasing rates from November 2023 to January 2024 (from $85 to $208), showing increased demand for containers in this lane.

“The significant spikes in shipping rates over the last three months signal a notable shift in the supply-demand dynamics, with demand recovery and capacity being increasingly tied up as the transit times via the cape of Good Hope increase by 2 –3 weeks. While the pre-Chinese New Year surge contributed, it was the disruptions caused by the Red Sea rerouting that served as the primary catalyst for the shooting up of leasing rates for containers,”

says Christian Reoloffs, co-founder, and CEO of Container xChange.

Fuel cost has also increased, roughly 20-23%, as ships have to travel a longer distance, notes Container Xchange. “Ultimately, the end consumer pays the freight cost. In the short term, usually, there is some intermediary that pays the bills because they have promised at a certain price, but ultimately, in normal circumstances, the price per unit is adjusted marginally to the end consumer when such disruption occurs,” adds Roeloffs.

Ease after Chinese New Year?

Geopolitical tensions such as the Russia-Ukraine conflict have also added to the rise in fuel price, insurance and operational costs of shippers.

Many experts say the situation can ease a little after the Chinese New Year — which falls on February 10 this year. Many businesses in the country’s global manufacturing hubs are closed or reduce operations during the holiday season, causing a slowdown in manufacturing and trade. Experts say this can lower demand for container shipping services, leading to a cooling period. But the global trade situation will not stabilise unless the Red Sea crisis is resolved, to begin with, they add.

Roeloffs expects the situation to persist for a longer period but agrees that the drop in demand usually seen during the Chinese New Year can give carriers time to reconfigure their network and adjust to the longer transit times.

No matter what, Indian MSMEs should be looking for new markets that are insulated from the geopolitical crisis. HEWA’s Srivastava suggests exporters focus more on Africa, Russia, South America, New Zealand and Australia. This will create a solution that can weather multiple geopolitical crises.