While traditional economic conflicts, such as worker strikes, have been on the wane, the vicious circle of low employability, leading to few jobs, mass unemployment and frustration, is now showing up in new forms of social conflict,” former RBI governor Raghuram Rajan and economist Rohit Lamba write in their new book Breaking The Mould.

They cite the conflict over reservations in Manipur and the substance abuse problem among Punjab’s youth as examples of how these frustrations are being channelled. The most recent instance of this could well be the Parliament security breach on December 13 when two men jumped into the Lok Sabha chamber from the visitors’ gallery and set off smoke canisters while another man and a woman sprayed coloured gas and shouted slogans outside.

The five men and one woman arrested for this protest were from different parts of the country and varied backgrounds, but reports revealed that, what they had in common, apart from an admiration for revolutionary Bhagat Singh, was the lack of a good, steady job.

They told investigating agencies that unemployment was one of the issues they were protesting about, bringing the spotlight back on one of India’s longstanding challenges. According to the annual data from the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), unemployment has fallen from almost 9% in 2017-18 to 5.1% in 2022-23.

But economists say unemployment figures are inadequate to capture the distress in India’s labour market, which includes issues like underemployment, low participation of women in the labour force and youth unemployment. For years, India’s demographic dividend was held up as one of the factors that would propel it on its journey of development.

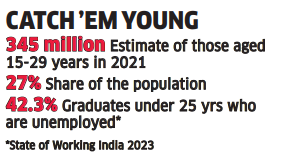

There were around 345 million Indians between the ages of 15 and 29 years in 2021, a 2022 government report estimated. But with insufficient jobs to fulfil their aspirations, the question is whether the demographic dividend will become a disaster and what India must focus on to avoid this. While parties have been promising jobs in national and state polls, will a failure to fulfil it translate into a shift in electoral choices?

CRUNCH THE NUMBERS

Radhicka Kapoor, professor at the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER), says, “If you look at the data of the last few years, you will find that though the unemployment rate is declining, the quality of employment in terms of employment status is worsening.

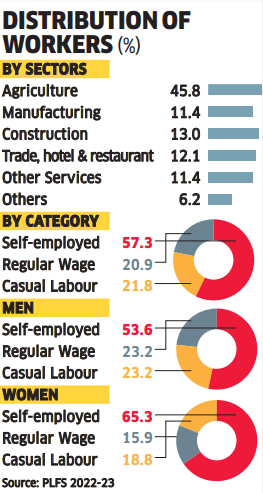

We are seeing a sharp increase in the number of self-employed in India and much of that increase is in the category of unpaid family helper.” PLFS data show 57% of workers were self-employed in 2022-23, up from 55% in the preceding two years. The bulk of the self-employed work in precarious jobs, as pushcart vendors, pavement sellers and the like.

This is because in developing countries like India, where there are no safety nets like unemployment insurance, people cannot afford to remain unemployed. “In that situation, where most people are not able to find jobs, they will create jobs for themselves working as own-account workers where they are self-employed,” says Kapoor.

When it comes to India’s youth, the picture gets worse. A report, “State of Working India 2023”, by Azim Premji University (APU) found that while unemployment is lower for all education levels post-Covid, it touched a worrying 42% for young graduates (less than 25 years).

This was 10% among 30-34-yearold graduates and 4.5% among 35-39-yearolds, indicating that graduates do find jobs but the nature of the jobs and whether these meet their aspirations are unclear. “The unemployed tend to be the ones waiting for some decent, regular salaried work—otherwise, if they wanted to, they could take up self-employment. But they choose to wait because they want a particular kind of work,” says Amit Basole, co-author of the report and head, Centre for Sustainable Employment, APU.

The kind of work the bulk of India’s youth aspires to is a government job. The Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), through its Lokniti programme, conducts nationwide surveys of the youth, where it has been asking them about the kind of job they aspire for.

“About 65% of Indian youth aspire for a government job. There’s been no change in this figure since we first asked this question in 2006,” says Sanjay Kumar, co-director, Lokniti.

“This is why, when there is an advertisement for a government job, you see a large number of people, even those with advanced qualifications, apply.” Neelam Azad, one of the six accused in the Parliament security breach case, would fall in the category that Basole and Kumar are describing.

A Haryana resident, the 37-yearold has multiple college degrees, including an MPhil, and has cleared the eligibility test for teachers in the state but has yet to get a job, according to reports. The others, too, do not have what might be called aspirational jobs.

Amol Shinde, 25, has not cleared recruitment exams to the armed forces and the police despite multiple attempts. Unable to continue his studies after Class 12 due to financial constraints, Sagar Sharma, 27, was driving an e-rickshaw. Manoranjan D, who has an engineering degree, was working on his farm, while Lalit Jha was with an NGO and Vishal Sharma was a driver.

“The allure of public employment remains strong and it’s easy to understand from the security point of view as well as the wage differential that exists between private and public employment for smilliar kind of work, especially at the lower end. For instance what a teacher in a government school earns compared with a private school,” says Basole.

With over half the workforce still in agriculture, the Indian economy is struggling with the structural transformation needed to move up the development ladder.

“Till 2018- 19 we were seeing a decline in those working in agriculture though not at as rapid a pace as one wants to see . But that structural transformation process has stalled, especially after the pandemic,” says Kapoor.

Then there is the fact that about 90% of those in the workforce are informally employed.

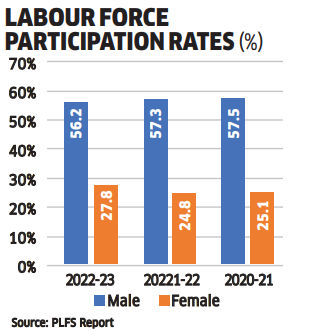

“This should not be what the workforce should look like. You should have a much larger share of regular wage workers.” To reap the much-vaunted demographic dividend, India would also need to improve the participation of women in the labour force, which was at 32% in the latest PLFS.

“If 50% of your population is not going to be participating in the transition of the economy, you can’t reap that dividend,” says Kapoor.

WAY FORWARD

Basole says that based on PLFS data and population projections, the absolute increase in the workforce between 2021-22 and 2022-23 was around 30 million, of which the absolute increase in regular wage workers was only around 2 million. There are two ways to look at the problem, says Basole.

“One, that we are not creating aspirational jobs. Two, we are not imparting the kind of education that can give them those opportunities.” India’s initiatives to promote manufacturing such as through productionlinked incentive schemes will play an important role, says Kapoor.

“The initiatives to boost manufacturing are very important because manufacturing accounts for just 11-12% of employment and 20% of GDP. Historically, no country has been able to become a developed country without going through the phase of manufacturing-led growth.”

In their book, Rajan and Lamba propose a different tack to create jobs: a value-added services export economy. “… while lowskilled manufacturing jobs are certainly welcome in India, putting all our hopes, resources and efforts into attracting such jobs betrays both a lack of ambition and imagination…. If, instead, we can enhance our ability to export services directly or export the services that are intertwined with manufacturing, we will create good jobs.”

This would, of course, require higher investment in education and healthcare, among other things. Considering the sheer scale of the unemployment challenge, India would need a mix of approaches. A first step would be to identify the mix of sectoral contributions to solving the employment problem, says Basole. “We need clarity on what we can reasonably expect from each of these sectors with scenarios of different growth rates.”

POLITICAL DIVIDEND

One acknowledgement of the unemployment crisis is in the manifestos of political parties, whether it’s the ruling BJP or the Congress and others in the Opposition. For instance, in 2013, before he was swept into power as prime minister, Narendra Modi had promised to create 1 crore jobs. While employment creation may figure in manifestos in 2024, too, the link between unemployment and voting has become tenuous. Kumar says there was a relationship between unemployment, price rise and voting choices, though not a very strong one, till the 2014 polls.

“If people were worried about growing unemployment and rising prices—both being connected—one could safely predict which way the voter was going to vote.” But that connection seems to have broken since 2016-17. “Though voters have anxiety over unemployment and price rise, they don’t tend to vote against the ruling party, be it in the national election or state election. This is no longer the main concern that shapes the choices of the Indian voter.”