The International Monetary Fund (IMF), in its annual Article IV Consultation Report released in December 2023, has warned India of crossing general government debt over 100% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

According to the report, the long-term risk is high because “the country needs considerable investment to improve resilience to climate stresses and natural disasters.”

In an unvarnished response, India has termed the warning as an extreme move, adding that risks from sovereign debt are very limited. It further asserts that despite multiple global shocks in the last two decades, India’s debt-GDP ratio has crossed 80% only twice, in 2005-06 and 2021-22. Moreover, it is declining since 2021-22.

The response by the Indian authority seems to be well in line with the facts and figures. However, there are many aspects underlying the caution which need to be examined in detail.

India’s debt-GDP ratio, during 2010-2022, has largely been in the range of 65-75%. There has been a large increase since 2020, reaching 88.5% in 2020 but it is again on a declining path since then. Even the range of 65-75 is a point of worry.

A study conducted by the World Bank argues that the debt-GDP ratio— for emerging economies exceeding 64% causes a negative effect on real economic growth. Given this stylized fact, the IMF warning should be considered as a red line as it has cautioned only when the debt-GDP ratio crossed 80%, which is way higher than the established threshold. However, debt-GDP ratio— above 80%, has crossed twice only, in 2005-06 and 2021-23.

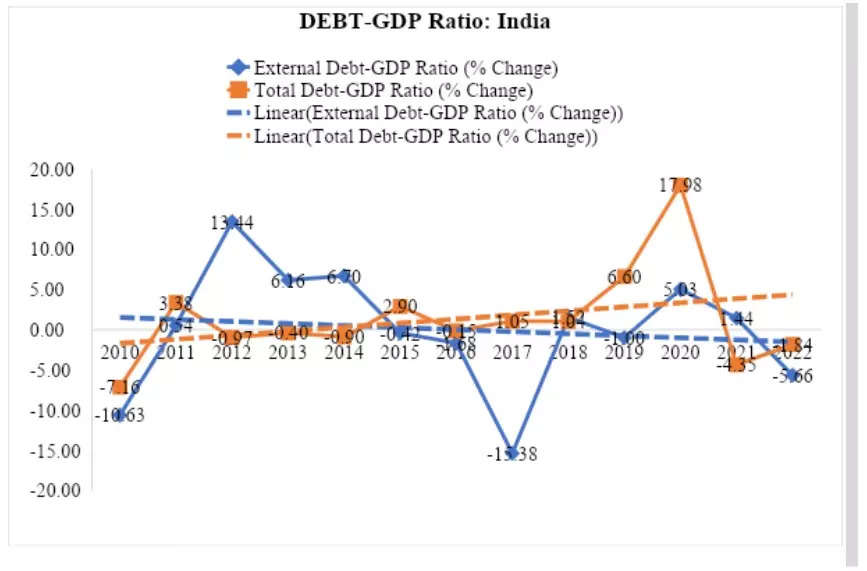

As far as the growth rate in total debt to GDP ratio and external debt to GDP ratio (Fig:1) is concerned, the former shows a moderate upward movement while the latter has a declining path. We do not see any persistence in the spike in the growth rate of the total debt-GDP ratio except in 2019-20, when it rose for two consecutive years, suggesting better debt management by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

Since 2010, the external debt to GDP ratio has been in the 18-24 range. The general trend in the growth rate of the external debt-GDP ratio has been declining since 2010 (Fig:1).

It indicates a declining reliance on external borrowings, which minimizes the exchange rate risks. As of September 2023, the total external debt consists of 54.7% in US dollar, 30.5% in Indian Rupee, 5.7% in Special Drawing Rights (SDR) by IMF, 5.6 percent in Japanese Yen and 2.9 percent in Euro.

Now, the question arises: do we have sufficient forex reserves and resources to fulfill these external debt obligations? The answer lies in the nature of forex reserves-external debt ratio. It has been quite volatile, mostly as a result of fluctuations in forex reserves.

During 2010-23, it peaked in the beginning (106.9 percent) and reached its lowest (72 percent) in 2015. I see here nearly a nip-and-tuck offset between forex reserves and external debts. Should we be worried about this?

The numbers tell a favorable story, but caution is required. First, almost 30% of India’s external debt obligations consist of Indian Rupees. Second, the share of short-term external debt hovers around one-fifth of total external debt (September 2023), and the ratio of short-term external debt to forex reserves comes to around 21.7 percent as of September 2023.

However, forex reserves are meant to fulfil many other obligations as well, mostly in cases of utmost needs, such as Current Account Deficit (CAD). India is not a Current Account Surplus country. In the July-September quarter of the Financial Year 2022-23, CAD rose to 3.8 % of GDP, which amounts to an enormous sum of USD 30.9 billion. However, in the corresponding quarter of the Financial Year 2023-24, it came down sharply to 1% of GDP. A high volatility in CAD warrants a considerable forex reserves’ back-up.

Moreover, the short-term external debt-forex reserves ratio has been hovering between 17-33% since 2010, reaching its highest in 2013 when it peaked at 33%. It declined to 17.5% in 2021, the lowest since 2010. It means that our need for forex reserves to fulfil short-term external debt obligations is not much. We need, at most, one-third of forex reserves to pay short-term debt in one go. However, again, considering the fact that India’s forex reserves are required for numerous other purposes mentioned above, caution is required if a further increase in external debt is noticed.

Another aspect of the discussion is the very purpose of the government’s borrowings in India. Although we do not have to consider the forex reserves here, other aspects need to be analyzed in a holistic manner.

Where do we spend the money taken in the form of debt? If the borrowed money is spent on capital expenditure, it may augur well for the economy by spurring economic growth through a multiplier. The multiplier for the capital expenditure (capex) is around 2.5, meaning Re. 1 spent on capex results in an addition to Rs. 2.5 in the national income.

The multiplier for revenue expenditure is close to 1. Another point to be highlighted is India’s expenditure priorities. Evidence shows that our expenditure priorities are misguided, leading to a huge rise in debt without any productive use of it. Consequently, limiting the scope of fixed capital formation and its compounded benefits through multipliers.

Almost 20% of India’s union government’s budget goes to debt servicing charges. If the trend continues, a vicious circle of Interest-Debt Trap is imminent. Some of the states, such as West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Haryana, and Punjab, have a ratio of interest payment to revenue receipt of more than 20. Their priorities on expenditure are also misplaced due to numerous reasons, such as political economy, excessive welfare, subsidies, and freebies.

We need to stress the following to better manage the government debts and their productive uses.

First, we need to keep the momentum of lower external debts, minimizing the exchange rate risks. A further reduction would be an added advantage. Second, a further decline in short-term total debt would help in focusing on capital formation— by having more long-term debts. It gives a longer time horizon for paying back the debts. Third, a shift in public expenditure priorities— towards capital formation, is required. It will usher in creating wealth (capital) and boosting economic growth through a multiplier.

(The author is Assistant Professor Economics at IIM Kashipur; Views are personal)