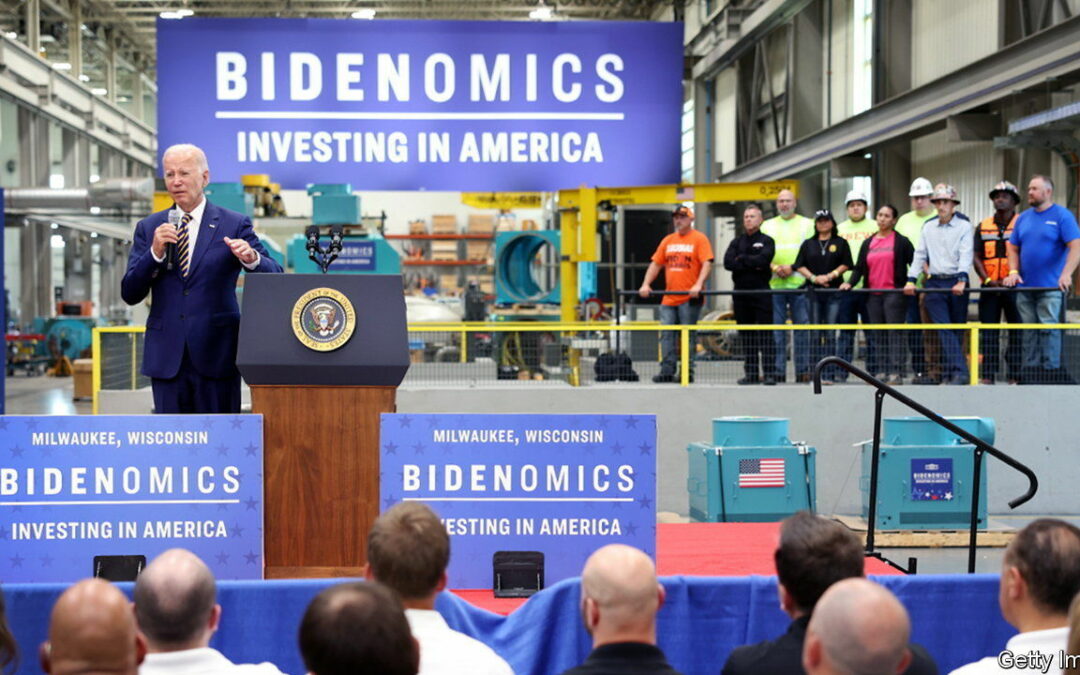

PRESIDENT JOE BIDEN has conceded that the name was a mistake: the success of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), his flagship legislation, should not be measured by its effect on inflation. These days the IRA is most often associated with decarbonisation—that is, by the few Americans who know about it. Mr Biden hopes to be re-elected next year, and this week he and his administration marked the anniversary of the IRA’s passage by touring the country to tout the benefits it has brought. What impact has the law actually had?

The IRA was so named in a vain attempt to rally support from voters, who in 2022 were worried about high inflation. Mr Biden had originally included climate policies in his sprawling Build Back Better agenda, which collapsed in December 2021 because of opposition from within his Democratic Party. Its revival—in the form of the much smaller IRA—was a surprising victory for Democrats.

The act has three broad components: it offers tax credits and funding to incentivise green-energy projects; it expands government-subsidised health care and lowers the costs of prescription drugs; and it tinkers with tax codes to raise more money from corporations. Not all of its provisions have gone into effect. The big projects it supports take time to plan and build. “Could”, “will” and “may” still pepper progress reports from the White House and from research firms.

But investments have begun. Most of the money spent under the IRA goes towards combating climate change. The earliest data show that companies that make clean-energy kit (like wind turbines and solar panels) are ramping up production. The American Clean Power Association, a trade group, says that 83 manufacturing plants have been announced since the bill’s passage. More than 50 will produce solar-power equipment. The rest will make wind-turbine parts or batteries. Together the projects represent $270bn of investment—equal to the previous seven years of clean-energy investment combined, according to the trade group. Firms have also announced $53bn of investment in factories making electric vehicles (EVs) and components they use, like batteries and chargers, according to a tracker run by Jay Turner of Wellesley College.

By the time Mr Biden took office in 2021, $50bn had already been announced in EV investment. The IRA has turbocharged these existing trends. Many of its subsidies are uncapped, meaning that, depending on how many projects are put forward by the private sector, its climate spending could cost anything from $369bn (the government’s projection) to trillions of dollars. Some of its subsidies are pegged to emissions targets, so—at least in the view of Wood Mackenzie, an energy consultancy—credits could be doled out as late as the 2060s.

Those incentives will have a dramatic impact on America’s ability to reach emissions-reductions targets. It pledged, in the Paris climate agreement of 2015, to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions by 50-52% from 2005 levels by 2023. A study published in Science in June projects that, by 2035, the IRA will be responsible for reducing greenhouse-gas emissions by 43-48% from 2005 levels.

The IRA’s other policies will also take time to be felt. The law will allow Medicare (government health insurance for people over 65) to negotiate drug prices, but not until 2026. In the meantime smaller fixes have gone ahead: the IRA capped at $35 a month out-of-pocket spending on insulin, a diabetes drug, by beneficiaries of some Medicare plans. Eli Lilly, a drugmaker, followed by voluntarily capping its insulin price.

In April Republicans in the House of Representatives voted to repeal the IRA, an empty gesture that the Democrat-controlled Senate would never have approved. In fact, Republican-voting parts of the country stand to benefit the most from the law. Many clean-energy projects will go to red states, be it to wind farms in the plains or hydrogen hubs in Texas or Utah (consortia in both states are bidding for the latter). Mr Turner’s tracker finds that $47.5bn of EV investments are heading to Republican districts, compared with $6.7bn destined for Democratic ones.

That means—at least with Mr Biden in the White House—that the IRA is probably safe from serious Republican opposition. Yet Democrats’ efforts to promote the law’s achievements have hardly been a success. A poll in August found that two-thirds of Americans had heard little or nothing about the IRA; just one-quarter knew about any of its climate subsidies. ■