- US economy is still sizzling, outperforming other regions

- Several factors behind this strength, such as heavy public spending

- For US dollar to enjoy a massive rally, it may also need risk aversion

Why is the US economy still so strong?

One of the most striking developments over the past year has been the extraordinary resilience of the US economy, despite the highest interest rates in a generation. The United States grew 2.5% last year, much faster than any other advanced economy, and by all indications continues to outperform in early 2024.

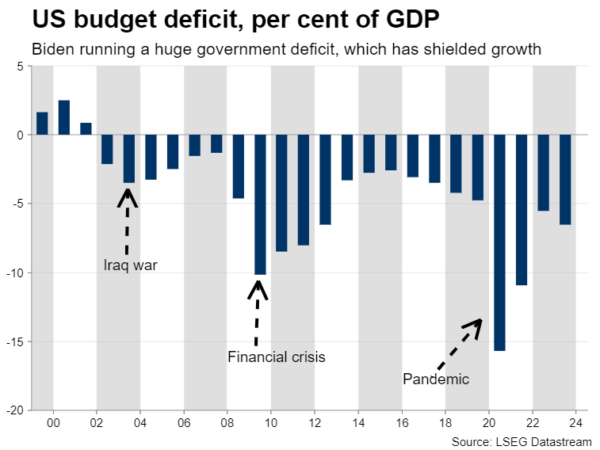

Several elements lie behind this strength. First and foremost, the US government is running an astronomical budget deficit, which amounted to more than 6% of GDP last year. This enormous public spending has shielded economic growth, but has also raised concerns about debt sustainability.

In contrast, most European nations are running much smaller deficits, which helps explain why growth in the euro area has been so anemic lately.

Immigration flows have powered the US economic machine too. With an influx of migrant workers coming in, the labor market continues to boom, cushioning consumer spending. And with wage growth finally surpassing inflation, the cost of living crisis has started to ease.

How the loan market is structured played a huge role as well. In the US, most mortgages are given at a fixed rate for 30 years. As such, many people locked in extremely low borrowing costs during the pandemic, insulating them from the sharp increase in interest rates that ensued.

Most other countries operate with adjustable rate mortgages, where payments reset every few years depending on interest rates. Therefore, many homeowners in Europe have started to pay higher monthly costs on their loans, squeezing spending even further.

Beyond all of this, America’s energy independence also helped safeguard consumers from the worst effects of soaring oil and gas prices following the invasion of Ukraine.

So why hasn’t the dollar skyrocketed?

With the US economy being stronger than other regions, this begs the question of why the dollar hasn’t mounted a tremendous rally. If the market was purely trading economic fundamentals, the dollar seems like the most attractive G10 currency at this stage.

It appears that developments in other financial markets have been holding the dollar back. The dollar often acts like a safe haven asset, since it is the world’s reserve currency. As such, the recent euphoria in stock markets has probably curbed demand for the greenback, preventing it from staging a fierce rally.

Another ‘problem’ for the dollar has been the collapse in natural gas prices, mostly because that is bullish for the euro. The Eurozone imports nearly all its gas, so when prices drop so dramatically, the euro receives a boost through the trade channel. This has allowed the euro to remain above water despite a deteriorating economy, in turn limiting the dollar’s advances.

What’s next?

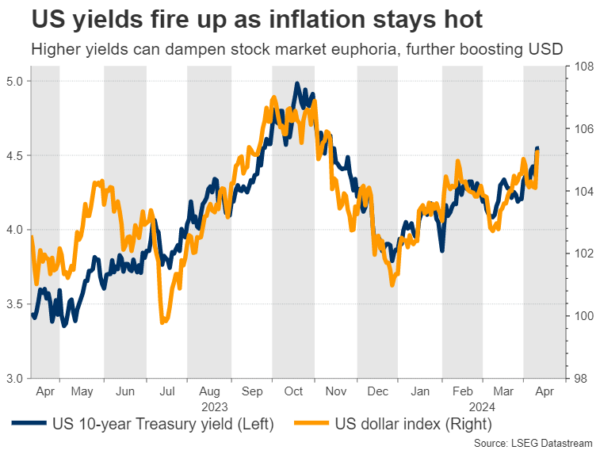

Looking ahead, we seem to be entering a period where the resilience of the US economy translates into persistently hot inflationary pressures, which might delay any rate cuts by the Federal Reserve.

The latest readings on inflation and the labor market certainly pointed in this direction, boosting the dollar in the process as traders dialed back on their rate-cut bets.

But if the price action over the last few months is any guide, economic fundamentals alone might not be enough to turbocharge the dollar. Instead, a full-blown rally might also require a period of risk aversion in the markets that fuels demand for safe havens like the dollar.

The stock market has looked bulletproof so far this year, as hopes of a soft economic landing joined forces with a rush to gain exposure to artificial intelligence shares. That said, equity valuations seem overstretched and a sustained unwinding of Fed rate cut bets that pushes bond yields even higher might be enough to trigger a sizable correction in riskier assets.

That might be the missing ingredient for the dollar to stage a fierce rally, especially if it happens during a period when foreign central banks begin to slash their rates.