Suppose you want to know how to become rich or how to become a good investor. How would you go about it?

A logical way to do it appears to be to look at the richest people in the world or the most successful investors, study the techniques that they have employed, and use them in your own life.

Seems logical, doesn’t it? To do as well in the markets as, say, Warren Buffett, Rakesh Jhunjhunwala or Ray Dalio you should just study their methods and replicate them. Seems simple enough.

This strategy, in fact, is not logical at all! It has an inherent and major logical fallacy – in fact, several of them – that can lead you to absolutely erroneous conclusions.

Before we plunge in, just a note, the examples chosen here have been chosen simply based on which investors and their methods have been studied well and extensively – basically the best known ones. They are, by no means, been chosen to prove a point or exemplify the ‘worst in category’.

First, are they buying the sort of stocks you think they are?

If you ask any follower of Warren Buffett to detail what kind of stocks he buys I am sure they can provide you a checklist of the kind: steady businesses mostly with great brands, predictable cash flows that can be forecast decades into the future, available at a reasonable price, etc. They may add: he does not buy businesses he does not understand or which are vulnerable to changes in technology.

All these are ‘principles’ extracted from writings by or about him.

Coca Cola which has been among his big holdings exemplifies this sort of stock (it is another matter that Coke has been a huge underperformer for 30 long years) but let us see what he actually holds.

As I write this in early 2024, almost 50% of Berkshire Hathaway’s total investment is in a single stock: Apple.

Does Apple really fit this bill? Sure it is a dominant player in mobile phones and certain devices – at least on the high end, but can anyone say with any degree of certainty what that business would look like at an industry level 10 or 15 years later.

As for being dominant, there was a time when Nokia and little Blackberry were considered unbeatable in the devices business – now consigned to the dustbin of history.

Now with Artificial Intelligence and many others new technologies moving very fast, who knows who the big winner of the next round will be. It has been very rare in the last few decades of technology that a winner in one round remains the leading player in the next round too.

And Apple is not the only example. Berkshire Hathway has invested very widely over the years in derivatives, in structured deals and so on. And often made a large chunk of money.

These are not the value stocks everybody thinks they buy. The sweetheart deals they got after the 2008 financial crisis in the likes of Goldman Sachs and later Bank of America are examples of this.

In fact Warren Buffett’s folksy, avuncular image allows him to get away with deals that would get others classified as vultures or sharks. He is always sniffing the waters when there is blood around.

Is their holding period what you think it is?

Again ask anyone who follows Buffett as to how long they think he holds a stock and the answer will be that his favourite holding period is forever. He thinks of himself as a part owner of the business and never intends to sell.

The reality? A majority of stocks that Berkshire buys are sold within a year: over 60% sold within 4 months, nearly 90% in 2 years.

The percentage of stocks held for over 10 years is less than 4% by number. This is the data as per study carried out for entire activity over the period 2006 to 2015. (study ‘Overconfidence, Under-Reaction, and Warren Buffett’s Investments’ by John S. Hughes, Jing Liu &Mingshan Zhang).

So the holding period is not forever – far from it. In fact, in one of his interviews he clarified that he meant the ‘hold forever’ mantra only for the businesses that Berkshire is majority owner of, which is obviously a small fraction of their holdings. And which really is making a virtue out of a necessity, because unless he has a strategic sale it is unlikely that he/ Berkshire can get out of those businesses.

Are the results as spectacular?

Another things that we take as a matter of belief without actually checking the data is that certain investors like Warren Buffett/ Charlie Munger and Ray Dalio are ‘successful’. But what does the data actually show?

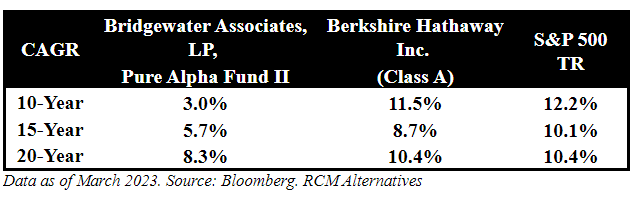

Berkshire Hathaway which was a Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger show has not outperformed the S&P 500 not for 1 or 2 years but for 10 and 15 years ending March 2023 – the latest point up to which data is available for Dalio’s Bridgewater. This is in spite of the huge crash in the US markets in 2022 which should have provided them alpha in their avowedly risk averse strategy.

While Berkshire results have at least been somewhat close to the market returns, Dalio’s Bridgewater has had a frankly disastrous run for a very long time. The fund has only compounded at 5.7% for 15 years as compared to 10.1% for the S&P 500. This means that $100 invested in the fund 15 years ago would have grown to only $230 instead of the $ 424 dollar figure reached for the same amount invested in the S&P 500.

Yet the glow of being smart and successful continues around these names because they can talk the talk.

Do you really understand how value is defined?

Many of the well known investors I am talking about are thought of as value investors and most people in the public market think they know what value investing means which is mostly buying stocks at low price to earnings or low price to book.

However for one, that is too restrictive a definition of value and as the example above shows with top holding being Apple, it cannot be called a Portfolio dominated by low valuation multiple or value stocks.

The interesting thing is that Benjamin Graham is considered the patron saint of value investing but in every edition of his book he kept refining the definition of value and in the later editions had spoken about how intangibles, like brand and technology, were contributing more and more to the value of the company.

This itself was written almost half a century ago and I am sure had he been alive he would have redefined what value was. However people do not go into the depth of even what he wrote and just go by the key or Cliff notes version and think they understand what value is.

Even more important is that Graham made almost all his money in Geico which is an insurance company and not the value stocks that he is associated with!

It is all about the timing!

We also spout many homilies about not timing the market, quoting some of these famous investors, but the well known success stories of investors are almost always a function of when they were in the markets.

In India if you had invested in the Sensex in 1980, your 100 rupees would have become about 700 rupees in a decade. From 2010 it would have become only 230 in 10 years.

If one looks at the well-known US indexes, we see this same pattern of very stark differences in compounding, not only in individual years but for decades altogether. Thus the S&P 500 compounded at 4.7 percent in the 1960s, 4 percent in the 1970s and then accelerated to 9.3 percent in the 1980s and nearly 15 percent in the 1990s.

Even if one looks at a 20-year period, a 100 dollars invested at the beginning of the 1960s in the S&P 500 would have risen to only $230 over the 20 years to 1980.

But equity investments rose nearly 10 times in the next 20 years of the eighties and nineties, making certain investors and fund managers appear brilliant.

That was the time when investors like Warren Buffett saw their biggest compounding. Not only that, the opportunities thrown up made others like Peter Lynch of Fidelity look outstanding.

As an aside, my respect for Lynch is not so much for his skill in stock picking, as for the fact that he recognised that the 14 year super run he had had at the Magellan Fund could not and would not be replicated and retired at the peak of his game when he was still in his 40s.

Not only do markets compound at different rates for even decades at a time, different types of stocks do well at various points in time.

Many who taught this philosophy of buying businesses that you understand (example Peter Lynch talking about buying the company whose pantyhose his wife loved), great brands, predictable cash flows etc are merely parroting stuff from books written in the 1980s when those were the kind of stocks that performed.

The fact is that no sector outperforms forever – not even steady consumer businesses. In India alone there have been even whole decades at a time when steady FMCG (Fast moving consumer goods) companies like Hindustan Unilever or Nestle India have underperformed the market hugely.

Now we know that the investors you admire may not actually be holding the kind of stocks you think they do, their holding period may be very different from what your impression of the same is, plus even worse, their results are nowhere close to the huge market-beating returns that you thought they had made.

Their money, in short, may have been made very differently from the public perception of it and may have more than a little to do with which period of the market they manage to catch.

But there is something even more fundamentally wrong in the very question we started with.

Let us say these investors had been very successful even in the last 10 or 15 years but there is still something really fundamentally wrong in the question we started with.

If you want to become rich or successful should you copy the methods of the richest and most successful investors in the first place?

To understand the flaw in this line of reasoning, you will have to read the second part. Out in a few days.

Note: This is part 1 of this series of columns.

(Disclaimer: Recommendations, suggestions, views, and opinions given by experts are their own. These do not represent the views of the Economic Times)