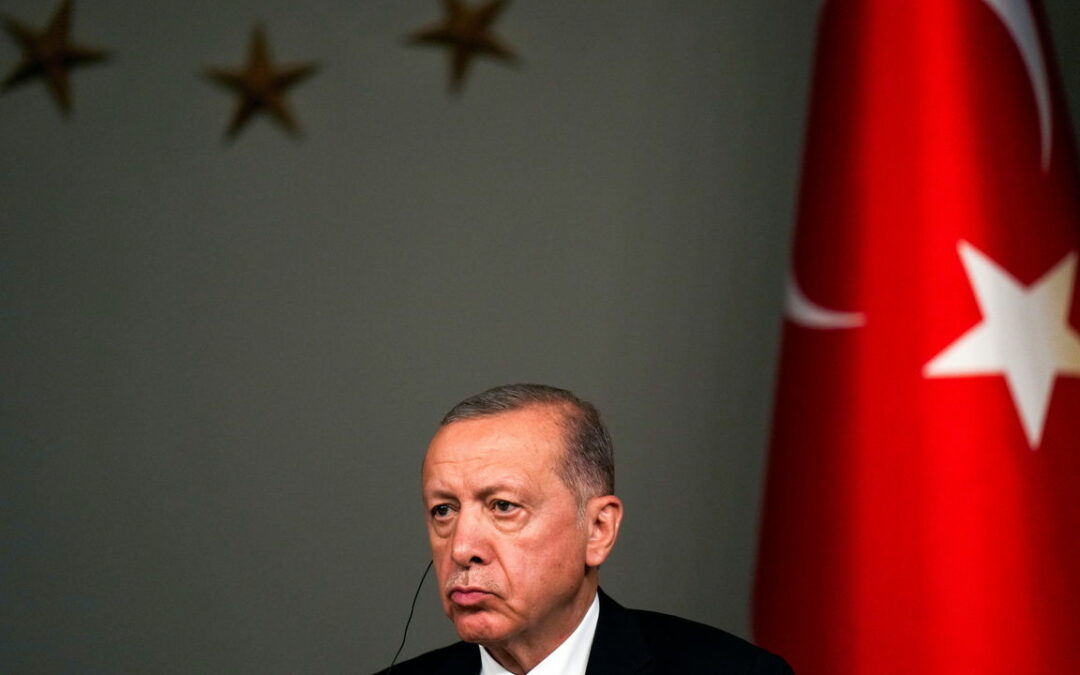

MEMBERS OF THE North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) would like to announce some good news at their annual summit. The military alliance will gather in Vilnius, the Lithuanian capital, on July 11th for a two-day meeting. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has reinvigorated NATO: in May 2022 Finland and Sweden applied to join it. Finland was admitted in April, but Sweden’s accession has been blocked by Turkey, one of NATO’s 31 members, ostensibly because the Nordic country harbours Kurdish separatists. On July 9th President Joe Biden told his Turkish counterpart, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, that he hopes to see Sweden join NATO “as soon as possible”. Why is Turkey holding out—and what does it hope to gain by doing so?

When Finland and Sweden asked to join NATO, Turkey opposed both bids, accusing the applicants of anti-Turkish activities. That included harbouring members of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a Kurdish separatist organisation based in Turkey, which is deemed a terrorist group by the EU and America as well as the Turkish government. In June 2022, at NATO’s summit in Madrid, Turkey struck a deal with Finland and Sweden: it would lift its veto in exchange for their lifting a partial arms embargo against Turkey, imposed after it invaded Syria in 2019. The Nordic pair also promised to crack down on financing and recruitment by the PKK in their countries.

That paved the way for Finland’s accession. Sweden has taken steps to meet Turkey’s demands: as well as lifting the arms embargo it passed an anti-terrorism law which bans participation in terrorist organisations (including the PKK). Yet Turkey accuses Sweden of not holding up its end of the deal. In January Mr Erdogan said he wanted 130 people to be extradited—up from an original request of 33. Talks soured when a far-right Danish politician burnt a Koran outside Turkey’s embassy in Stockholm, the Swedish capital, on January 21st. Koran burnings, in protest at various issues, have continued, angering several Muslim countries. In a phone call on July 9th Mr Erdogan told Mr Biden that although Sweden had taken “some steps in the right direction” these had been “nullified” by anti-Turkish demonstrations.

But Turkey appears to have other reasons for blocking Sweden’s membership. On their recent call Mr Biden and Mr Erdogan discussed Turkey’s request to buy American F-16 fighter jets. America’s Congress, which would need to approve the sale, has shunned Turkey since it bought a Russian S-400 air-defence system in 2019. America cancelled the sale of its F-35 stealth fighter jets to Turkey, fearing that Russia could glean intelligence about its most advanced warplane. (Antony Blinken, America’s secretary of state, claims Turkey’s request for jets is “totally unrelated” to Sweden’s NATO bid).

Mr Erdogan has recently cited another reason for stalling: EU membership. Turkey has been formally recognised as a candidate since 1999, but accession talks got stuck years ago. On July 10th Mr Erdogan said he would ratify Sweden’s membership of NATO if his country were admitted to the bloc.

NATO leaders had hoped to clear the way in time for the Vilnius summit. Sweden’s accession has already been ratified by all other members, barring Hungary, the other opponent, which is expected to fall in line if Turkey drops its veto. Sweden has been offered interim assurances of assistance were it to be attacked by several NATO members, even though it is not formally covered by Article 5, the alliance’s mutual-defence clause. On July 10th Mr Erdogan was due to meet the Swedish prime minister, Ulf Kristersson, for last-minute talks. Turkey’s leader may feel powerful given the leverage that he has—but his obstinacy is eating into the goodwill he has in the West. ■